Everyone else is wrong, right?

Behind the scenes, NSW health officials seem aware that the Cass review poses a credibility problem for them

Internal doubt

Someone in the health department of NSW, Australia’s most populous state, wanted to know why.

Both NSW Health and England’s NHS had commissioned reviews of the evidence for paediatric gender medicine. It’s the same evidence base internationally.

The result of England’s 2020-24 Cass review—which found the evidence “remarkably weak”—was an end to routine use of puberty blockers for gender-distressed children.

In NSW, the 2023-24 Sax Institute’s review said the evidence showed blockers to be “safe, effective and reversible.”

And NSW Health, the state government agency, continues to expand its “gender-affirming” supply of blockers and cross-sex hormones for young people referred to in its service framework as “tranz,” “non-binary,” even “poly gendered.”

In April 2024, however, someone in NSW Health wanted to know, why did our Sax review have such a different outcome from the Cass report?

This doubt has come to light in documents released to GCN under the Government Information (Public Access) Act.

It is still a live question, and not only in NSW.

In the state of Queensland, psychiatrist Ruth Vine has just been appointed to lead what is potentially Australia’s first serious independent review of the evidence for puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones.

Under her terms of reference, she “may consider” both the Cass and Sax reviews.

And the Sax Institute review has been put on the federal political agenda by Australia’s Health Minister Mark Butler, who told journalists in January that this document was summer holiday reading for him.

“[I]t is not, as some have suggested, just the absence of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that results in the evidence [for hormonal treatment of gender-distressed young people] being mostly rated as very-low certainty.

“Rather, it is the absence of reliable studies across all study designs; indeed, a poor-quality RCT would do little to improve the certainty of evidence.”—Australian psychiatrist and researcher Alison Clayton, editorial, Archives of Disease in Childhood, 12 March 2025

Sitting on Sax

Back in April last year, when that unnamed NSW health official put the obvious question, it appears the Sax review had been finalised for about two months—and it was not to be made public for another six months.

On April 16, almost a week after publication of Dr Cass’s final report, the NSW official emailed the Sax Institute in Sydney to say that a colleague wanted to know “why our final conclusions are different to the UK’s?”

This email, released to GCN, notes the “decision on puberty blockers by the NHS commissioning team.”

That March 11 decision of the NHS, informed by the Cass review, said—

“We have concluded that there is not enough evidence to support the safety or clinical effectiveness of [puberty blocker drugs for gender-distressed minors] to make the treatment routinely available at this time.”

Dr Cass’s four-year inquiry was the world’s most comprehensive and included multiple systematic reviews of the evidence published as peer-reviewed papers.

In the April 16 email exchange between NSW Health and the Sax Institute, the unnamed official states what she thought might explain the starkly different outcomes and the Sax staffer replies with in-line commentary.

The official begins by suggesting that the 2020 systematic evidence reviews undertaken for Dr Cass by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) “had a very limited scope of what was considered relevant and it was a comparative approach. The questions asked were very different to ours and so it is not really comparable.”

Sax staffer: “That is correct.”

Nothing is said about the fact that the Sax review, called an “evidence check,” is also at odds with systematic reviews of the evidence undertaken independently in jurisdictions such as Finland, Florida and Sweden—reviews resulting in more cautious, less medicalised treatment policy than in NSW.1

What does get a mention in the April 16 exchange between the NSW official and Sax is the second round of Cass-commissioned systematic reviews undertaken by the University of York, which also gave results at odds with the Sax evidence check.

The NSW official suggests the difference is explained by Sax using “a wider criteria in terms of evidence.”2

The Sax staffer appears unsure about what is being suggested, but replies that there were indeed differences in how the population of patients was defined for the review Down Under.

The staffer also cites “differences in study design,” noting that the Cass reviews excluded a (lower quality) category of studies known as “case series,” which by contrast were included in the Sax evidence check.3

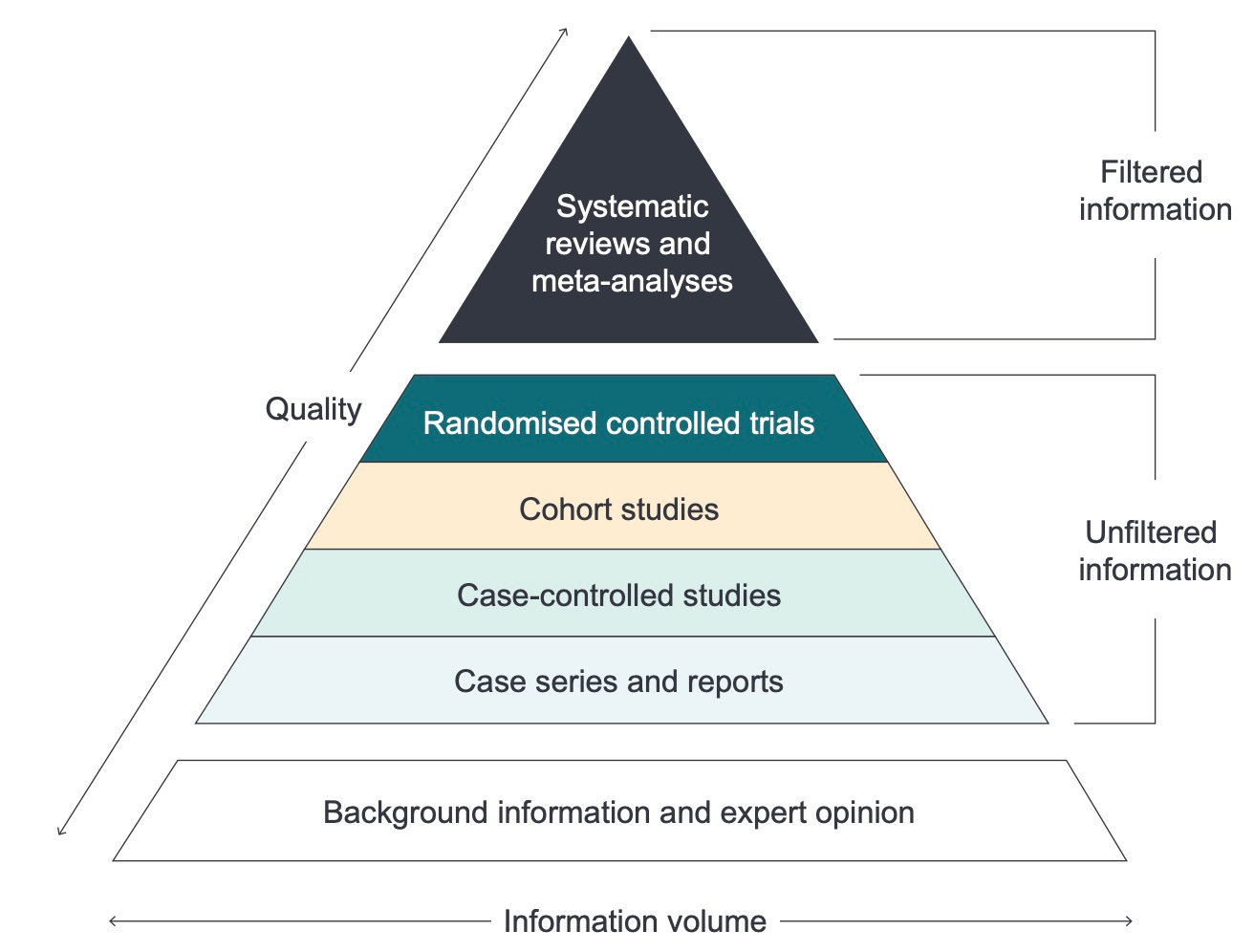

Graphic: The evidence hierarchy, with stronger studies at the apex

Not all evidence is equal

But the April 16 email exchange with NSW Health says nothing about a questionable Sax device that exaggerated the quality of the evidence.

To lend credibility to its evaluation of the scientific literature for blockers and hormones, Sax used a well-known Australian system for rating the evidence.

“All [study] citations were ranked according to the established National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Levels of Evidence to assess the robustness of the included studies,” the Sax evidence check says.

Graphic: Evidence ranking system, with gold-standard studies at the top, from the NHMRC

The trans tweak

Paediatric gender medicine is a field known for its weak and uncertain evidence base.

Yet Sax reported the good news that 16 of the 82 studies in its literature review were good enough to be ranked as Level I, the top rung on the NHMRC hierarchy.

In the NHMRC system, a Level I study is a systematic review of Level II studies, which in turn are randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Systematic reviews and RCTs are considered the gold standard for evidence.

But the Sax evidence check comes with a confession: Level I has been redefined.

In small print, the report of the evidence check says those 16 Level I studies do not include systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials, “although this is the technical NHMRC classification.”

The result—as pointed out in an article for GCN by psychiatrists Jillian Spencer and Patrick Clarke—is that in some cases the Sax evidence check assigns the highest level of evidence to articles “by authors undertaking a narrative review of poor-quality, small, methodologically flawed studies located through a systematic search.”4

“The studies included in these [narrative] reviews were discounted as too unreliable to guide clinical practice by the NICE and Cass reviews,” Drs Spencer and Clarke write.

“This approach has the consequence of devaluing the Sax report’s recommendations by introducing unreliable findings from historical studies that are at odds with the Sax report’s stated intention to derive its findings from literature published between 2019 and September 2023. For example, in one such review, eight of the nine studies were published prior to 2019.

“The inclusion of these reviews is also at odds with Sax’s claim to exclude articles with ‘mixed-age populations with no sub-analysis of people ≤ 18 years of age or where the proportion of participants ≤ 18 cannot be determined.’ Several of the articles included in these [narrative] reviews had mixed-age subjects with no sub-group analysis.”

Client-cum-funder

The Sax Institute had a conflict of interest, being financially “dependent” on its client, NSW Health, a government agency expanding the hormonal treatments to be evidence checked.5

The results of Sax’s evidence check were released in September last year as a 193-page main report and a four-page summary; neither document discusses the Cass review.6

The news coverage by Australia’s national broadcaster, the ABC, ran with the headline, “Puberty blockers a ‘safe, effective and reversible’ form of gender-affirming care …”

GCN sought comment from the Sax Institute and NSW Health

An often-repeated activist critique of the Cass review is that it supposedly recognised no quality evidence apart from randomised controlled trials (which are almost non-existent in youth gender dysphoria). This is false. In systematic reviews for Dr Cass, the University of York used a measure designed for rating the quality of non-randomised studies, as journalist Jesse Singal has reported. In a Chilean webinar earlier this year, Dr Cass said that even when moderate-quality studies were evaluated in systematic reviews, the evidence for these hormonal treatments “was still really, really weak.”

The first-round 2020 NICE reviews for Dr Cass stipulated that, “If no higher-level quality evidence is found, case series can be considered.” The second-round University of York reviews, published in 2024, excluded case studies and case series.

A narrative review may be less transparent and more prone to bias than a systematic review. The Sax Institute markets its evidence check as “a fast and accurate summary”; it is not a systematic review.

A note in Sax’s latest financial statements declares: “The Sax Institute is dependent on the NSW Ministry of Health [NSW Health] for a significant contribution to fund corporate costs. The Ministry provides funding on a quarterly basis. Funding agreements are entered into for five-year periods with the current agreement in effect from 1 July 2023 to 30 June 2028.”

When the top tier of evidence supporting a medical intervention (a randomised controlled trials (RCT)) is absent, the justification for applying that medical intervention is severely limited to scenarios such as the use of an experimental drug in a terminally ill person (some cancer therapies might apply and patients would be informed of the experimental nature of the therapy)

In the absence of top tier evidence to support the of puberty blockers cross sex hormones and irreversible mutilating surgery in children burdened with a diverse range of mental health conditions would be a violation of the most basic tenet of medical practice.

It’s all because of stupid, vain pollies handing out money to career activists. Imagine if parents and detransitioners, and staff fired from their jobs for raising objections, and women who’ve had their awards and prizes taken by men- if they could all bring a class action against government ministers for misconduct / failing to act impartially.

https://ladykitkowalski.wordpress.com/2022/11/19/how-much-are-we-paying-for-these-23-lgbtiq-charities/