Trial and tribulation

Sharp and polarised dissent has only reinforced the view of Hilary Cass that a clinical trial of puberty blockers is the right choice

A right to rigour

Gender care reviewer Hilary Cass has reaffirmed her support for a clinical trial of puberty blockers in the United Kingdom, insisting that any treatment offered to gender-distressed children must be tested by the normal, rigorous standards of medical science.

In a bilingual webinar on Wednesday for Chileans and other Spanish speakers, Dr Cass said the factors favouring a trial included the possibility that some minors might benefit from puberty suppression, and she suggested the results of the trial could feed into a broader program of research to improve and better target healthcare.

In March last year, as a consequence of the Cass review, England’s National Health Service (NHS) announced the end of routine use of puberty blockers for gender distress, confining this off-label treatment to an ethically approved clinical trial, which is expected to begin recruiting participants in the northern Spring.

Dr Cass, a former president of the UK college of paediatrics, told Wednesday’s webinar that the job as first proposed to her by the NHS was a straightforward six-month review of the scientific literature, something she said “a sensible person” might have stuck to.1

But she became “more worried” about the dramatic spike in patient numbers at the London-based Tavistock gender clinic with its long waiting list and lack of access to mainstream healthcare.

After a four-year review, the world’s most comprehensive study of youth gender distress, Dr Cass said her final report issued in April last year had been met with “a massive, funded disinformation campaign,” especially from the United States in the lead up to November’s presidential elections.2

“Much of what was said [during this campaign] is completely unrelated to what the [April] report said,” she remarked, citing as an example the false claim that the Cass review had “thrown away” any research on puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones “that wasn’t a randomised control trial.”

Like systematic reviews independently undertaken since 2019 in Finland, Sweden and the American state of Florida, reviews commissioned by Dr Cass found only weak and uncertain evidence for the use of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones as a therapy for gender distress among the minors.

“What the systematic review tries to do is say… if you get rubbish [research] in, you get rubbish out. So, we’ll take only the good studies and collate the responses from the high-quality and the moderate-quality studies, and we get rid of the poor-quality studies.

“But even when they did that [as part of the Cass review], the evidence [for these hormonal treatments] was still really, really weak… even compared to other areas in mental health, which is difficult to research. It stood out, how poor the quality of the [gender medicine] studies was.”—Dr Hilary Cass, Chilean webinar, 8 January 2025

Self-fulfilling prophecy

In the webinar, initiated by the Chilean parents’ group Kairós and hosted by the psychology faculty of Chile’s University of Development, Dr Cass warned of the “very high risk” of children becoming “depressed and possibly suicidal” if they come under the influence of a misleading narrative that the puberty blockers to be denied them are essential to relieving their distress and to accessing gender transition.

She counselled against blockers being sold as a “magic bullet,” and noted a recent comprehensive registry study from Finland that suggests the suicide risk in gender clinic populations is driven not by gender distress itself, but by psychiatric co-morbidities for which there are already evidence-based interventions.

More generally, Dr Cass said the thrust of her review was to use existing knowledge to support young people with distress and “to create the conditions where we can do the research and improve our understanding and improve the care over time.”

There is uncertainty about the causes of an unprecedented surge in gender clinic caseloads internationally since 2010-15 and a flip in patient profile from males presenting with gender dysphoria in early childhood to chiefly female teenagers with no such history and often pre-existing psychiatric issues.

Dr Cass emphasised the imperative for open debate in this hot-button field.

“The most important thing in this area, which has been a real problem internationally, is we mustn’t shut down debate,” she said.

“Where people are afraid to speak up or get attacked for speaking up or for questioning things, then that’s where it becomes really dangerous… in medicine, you put people at risk if you can’t question.”

“The thing that has been very good in the UK is that both our main parties [Conservatives and Labour] have supported [the Cass review], the left and the right have both supported it… And so, it took it out of being a political football, whereas in the US… if you’re in a Blue [Democratic] state or a Red [Republican] state, that determines your attitude.”—Dr Hilary Cass, Chilean webinar, 8 January 2025

Trial and error

Dr Cass highlighted the sharp disagreement about the puberty blocker trial recommended by her review and supported by the UK Labour government’s Health Secretary, Wes Streeting.3

“There’s already quite polarised views [in the UK]… Some people say it’s not ethical to say to young people, you can only get this drug by joining a trial. Some people say that’s coercion, and it’s not right, and you should have these medications freely available,” she said.

“And on the other side are some people who say that, after years, you haven’t shown any benefit of these drugs, and you’ve shown possible harm—so, it’s not even ethical to consider a clinical trial, [blockers] should just be stopped.4

“And so, with those two views being so extreme, I think that demonstrates that we do need a trial.”

She said in her view, “social justice” for gender-distressed young people required that their care be supported by the “same standard of evidence” as for any other patient group.

“If I suggested giving your child a treatment for asthma which has as poor a research base as these [hormonal] medications do for gender dysphoria, you’d say, absolutely no way,” she said.

“I think the only way that we can move forward in this area is by saying, how would we approach this for any other area of medicine, and to make sure we match the standards.”

Asked during the webinar about the possibility of a minor seeking to join the UK puberty blocker trial without parental agreement, Dr Cass said the consent of parents would be necessary for a child under 16 to take part in a research study.

“If [this conflict] did arise, then where the clinician strongly felt it was in the interests of the child to go on to the puberty blockers and the parents weren’t prepared to give consent, I guess it would end up in court—but I think that’s a not a very likely scenario,” she said.

“This is not a black and white issue. Some people will say, all of these children are trans children, and they need to get on medicines, and other people will say, this is all social contagion and social media… Both of those extreme views are wrong.”—Dr Hilary Cass, Chilean webinar, 8 January 2025

Known unknowns

Asked to comment on the claim that puberty blockers are reversible, Dr Cass said: “We think physically, most things go back to normal [if a young person stops taking blockers]. We don’t understand about the psychological and the neurological impact.”

Neurologically, she pointed out that adolescence was a “very busy time” for brain development.

“You’re getting your frontal lobe development—so your higher-level decision making, how you make judgments, how you weigh up risk and so on, that complex, higher-level thinking.”

She said it was unknown whether or not suppression of natural sex hormones with puberty blockers denied the adolescent brain a critical window of development, with long-term cognitive deficits.

“We also don’t know whether your bone development catches up, or whether you have weaker bones in the longer term,” she said, referring to the fact that puberty is normally a period of very rapid increase in bone density, setting up a young person for life.

“And we also don’t know whether [puberty suppression] has a permanent effect on your psychological development,” Dr Cass said.

“If you think about what’s happening in puberty… you’re working out your sexuality… I mean, it must have some impact that other young people of your age are going on having sexual experiences and developing psychologically, and you’re not. We don’t know what the long-term psychological impact is.”

She said it was unclear whether puberty blockers changed the trajectory of development of sexual orientation and gender identity, potentially locking the child into a medical pathway.

“The hardest message for [the Cass review] to get across is, this is a heterogeneous group. These children are not all the same. They’re a very mixed group with very broad-ranging presentations and complex needs that [go] well beyond the gender-related distress—and that needs to be reflected in the service offer available to them.

“A significant percentage have autism and/or ADHD. There [are] high rates of adverse childhood experiences… high rates of trauma and family stressors, and quite a range of mental health issues, including depression and anxiety.”—Dr Hilary Cass, Chilean webinar, 8 January 2025

Who benefits?

Dr Cass said there were “some young people for whom [puberty blockers] may be the right thing, and that’s why I said there should be the [clinical trial] research study.”

She said puberty suppression and medical transition might benefit “a small group”, notably some patients with the once-classic gender clinic profile—males who present with gender distress in early childhood—and have socially transitioned to a female identity when still young.

“But within that group of [chiefly female] young people who first present in their teenage years, for many of them [gender distress] is a transient phenomenon that might resolve as they go through teenage years, or they may just continue to express their gender flexibly, but a medical transition is not the right thing for them.”

Dr Cass acknowledged the problems with the foundational “Dutch protocol” of the 1990s that inspired gender clinicians internationally to offer puberty blocker-driven gender change for minors.5

She said Dutch psychologist Dr Peggy Cohen-Kettenis had felt that transgender-identifying adult males did not do well psychologically because they failed to “pass” as women in society.6

“She thought that if you blocked puberty very early, before these irreversible [masculine] changes had appeared, you would have a better cosmetic outcome,” Dr Cass said.

But Dr Cass noted that the Dutch research had managed only “small improvements” in mental health for minors on puberty blockers, and the rationale that puberty suppression would give children “time to think” about future steps had been undermined by data showing that almost all patients begun on blockers proceeded to cross-sex hormones.

Moreover, she said clinicians had told her during her review that it was hard to know which children with early-onset gender dysphoria would grow out of it without medicalisation and which would persist with a stable opposite-sex identity into adulthood.

This inability to predict underpinned the old, more cautious “watchful-waiting” treatment approach, which has been sidelined by the more dogmatic “gender-affirming” model.

“For one young person, they may go through a period of gender questioning and then find that actually they were really sort of struggling with their sexual orientation,” Dr Cass said.7

“And when they come out as gay, maybe they feel less confused about their gender identity. For another young person, they will have a stable trans identity.

“For [still] another young person, they’ve expressed their distress about their family trauma through their gender in the same way that somebody might express their distress through an eating disorder.

“So, because there are so many different ways into gender distress or gender questioning and so many ways out, I think it’s going to be a long time before we understand the right individualised psychological care for each child.”

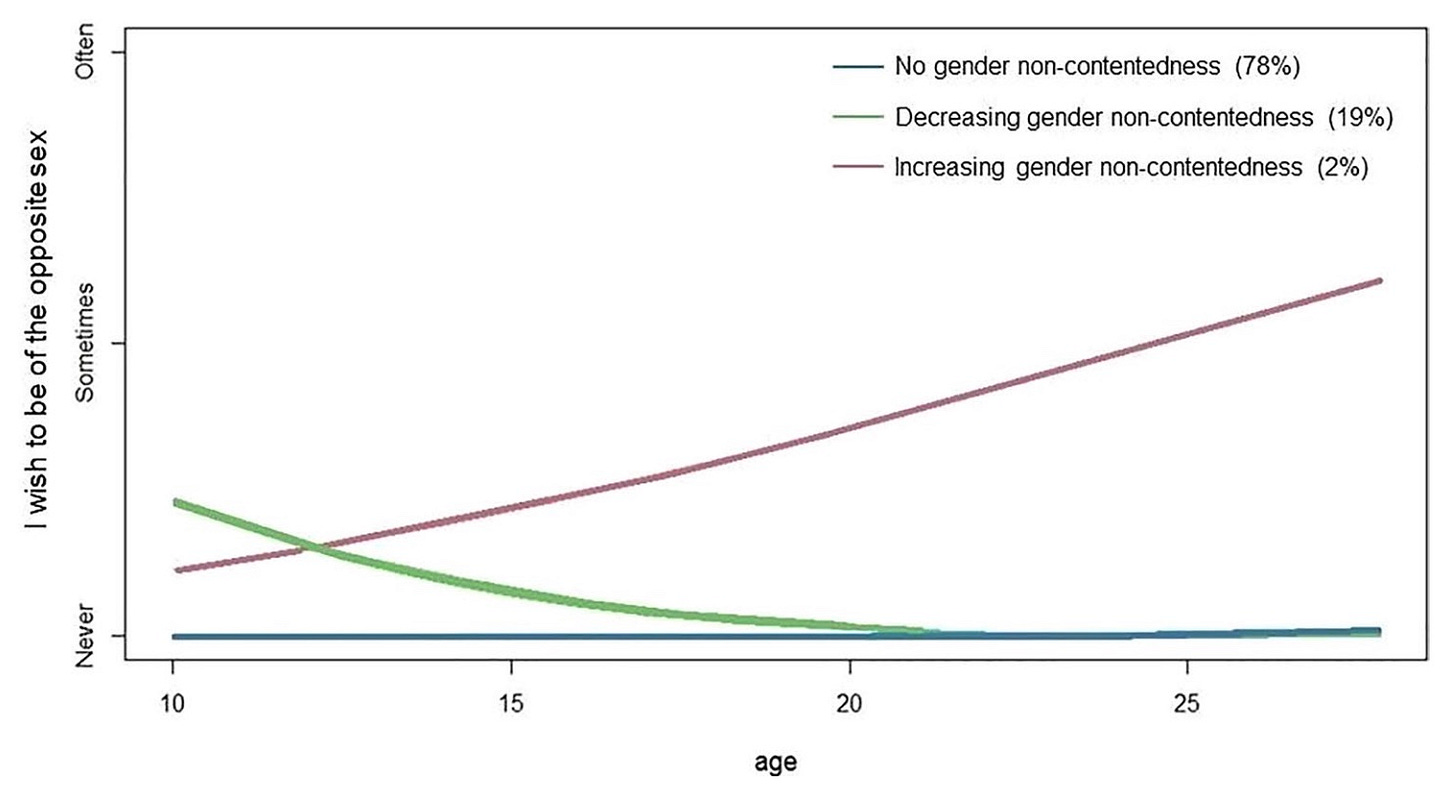

Chart: Differing trajectories of feelings about birth sex in three groups of young people over time. (Dr Cass used this chart during the webinar)

“One of the problems we’ve had in UK schools is that sometimes the school has done a social transition, changed the child’s pronouns, changed their names on the school register without telling the parents, and then there’s a secret between the school and home…

“I understand they are worried that some children may come to harm if their parents find out that they’re identifying differently from their birth gender.

“But you should start from the assumption that [the vast majority of] parents are well intentioned… And we know that children thrive better if they’re supported by their parents and so the presumption should be to try and involve the parents, involve the primary care practitioner, the school nurse…

“It’s really important that schools are involved in research and thinking about these young people… in any one classroom, large numbers of kids are gender questioning… [At] the NHS, we’re seeing just a tip of a pyramid. We’re not understanding the natural history of this condition in the majority of kids.”—Dr Hilary Cass, Chilean webinar, 8 January 2025

A wider view

Dr Cass’s advice for clinicians attending the webinar was to avoid a gender-only focus and to seek “to help children to thrive and achieve their life goals.”

“The immediate goal of any treatment plan must be to address the distress and any barriers to participation in everyday life, because many of these young people were out of school,” she said.

“[If] there was family breakdown, there were all sorts of other problems going on for them, and if you just think about their gender, you are not helping them to thrive.

“We worked with our clinical expert group [during the Cass review] to develop a holistic assessment framework where the first thing was to assess any immediate risk that’s a mental health risk or a safeguarding risk, and then determine the complex care needs of the children referred to the service.”

Dr Cass said the Tavistock clinic, which was the sole specialist gender service for England and Wales, had been criticised for being “locked into a groupthink—that they were only seeing these children through a gender lens.”

“I think they got caught up… they almost didn’t have time to think, you know, the kids were pouring in… there was lot of adverse press in the UK, because people in that [Tavistock] service who disagreed with the way that things were being done, they ended up raising concerns—whistleblowing, as we call it—and then leaving the service. So, the service got more and more focused on a single view.”

Meanwhile, Dr Cass said, local mental health services had been “disempowered” and told that “the only thing to do is affirm these children in their identity and send them on [to the Tavistock].”

“So, these young people were not getting the ordinary [mainstream care, such as an] autism diagnosis, help with trauma, help with depression, help with eating disorders that other children were getting.”

Dr Cass said the message for local mental health clinicians should be that these gender-distressed kids “are the same kids that you’re already seeing in your [own] clinic.”

“We must normalise care. We must provide for [these gender-distressed children] exactly the same standards of care as for any other child.”

She said the new network of post-Tavistock gender services—built into mainstream specialist health services for children with expertise in safeguarding, mental health, neurodiversity, trauma, eating disorders—was “designed to guard against” groupthink.

“What we are trying to set up is a learning environment, what we call a ‘community of practice,’ where you’re all learning together and sharing experience,” she said.

Dr Cass had already retired as a paediatrician and was planning to learn saxophone and do some creative writing.

Probably the most widely cited critique of the Cass review was the document misleadingly promoted as the “Yale white paper.” Its credibility has been challenged by a peer-reviewed analysis in the British Medical Journal and by a three-part article by journalist Jesse Singal. The Cass review published an FAQs page to counter disinformation.

In December last year, Mr Streeting said it was “a scandal that [puberty blocker] medicine was given to vulnerable young children, without proof that it was safe or effective, or that it had gone through the rigorous safeguards of a clinical trial.”

The key studies for the Dutch protocol have recently come under closer scrutiny.

A long-term follow-up study in Sweden, using comprehensive registry data, found that post-surgical transsexuals had a suicide rate 19 times higher than the general population. This 2011 study by Dhejne et al concluded that, “Persons with transsexualism, after sex reassignment, have considerably higher risks for mortality, suicidal behaviour, and psychiatric morbidity than the general population. Our findings suggest that sex reassignment, although alleviating gender dysphoria, may not suffice as treatment for transsexualism, and should inspire improved psychiatric and somatic care after sex reassignment for this patient group.”

Data from the Amsterdam and Tavistock clinics, together with more recent surveys of detransitioners, suggest that a significant number of young people presenting with gender distress are same-sex attracted.

I’m surprised we haven’t seen any reporting or documentation of the ethical clearance. I’m assuming it has been cleared if, as Wes Streeting says, they are to start recruitment in the next few months.

I am disappointed too. There is no way these clinicians should be experimenting on children. Isn’t that what these people have been doing? And it’s a rank failure. Case closed.