Sleight of hand

A sharp decline in new referrals at Australia's most influential gender clinic masks intense medicalisation and the diversion of patients to other services

Dianna Kenny

There has been recent speculation within Australia and internationally that the numbers of young people identifying as trans or non-binary and who present to gender clinics and hospitals for gender transition interventions are declining.

In October 2025, the Society for Evidence-based Gender Medicine (SEGM) analysed recent surveys from the US claiming that trans identification and non-binary identification were in “free fall.” SEGM begs to differ, arguing that the analyses reporting decreases in identification are the result of poorly worded survey questions and inappropriate statistical weightings being applied to the data. Their own analysis of the US college students’ survey (NCHA) comprising 2.5 million students (average age=20; female=70%) attending 1,000 higher-education institutions over the last 25 years showed the opposite result i.e., that trans/non-binary identification was at its highest yet—from 4.7% to 6.7%—compared with 0.1% in 2015, with 8% females and 5% males not identifying with their biological sex.

Data are sensitive to small variations such as change in wording of survey questions over time. In 2015, in the NCHA survey, the question wording changed from “What is your gender?” to “Do you identify as transgender?” after which there was a sharp rise (three times greater) from 0.5% to 1.6% in the number of participants identifying as transgender. Last month SEGM updated its sceptical analysis of US college data and debunked an article in the Swiss media which had declared “the gender revolution is over.”

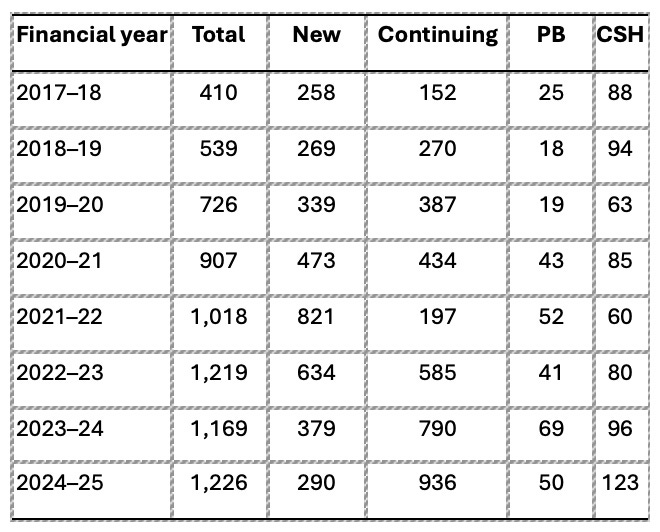

Another question of interest is whether the numbers of young people enrolling in gender clinics and receiving treatment have changed over time. To assess trends in gender transition interventions, all data for total patients, new patients, continuing patients (i.e., total n minus new n), numbers commencing puberty blockade (PB), and numbers commencing cross-sex hormones (CSH) were obtained under freedom of information law from the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) in Melbourne, Australia, for the period 2017-2025. Table 1 shows the annual numbers by category and year.

Table 1: RCH patient data 2017-2025

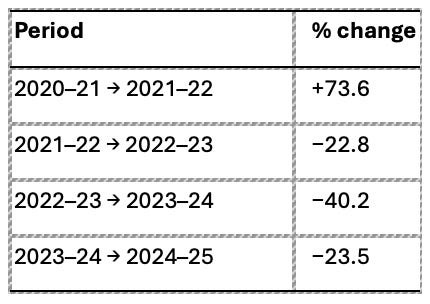

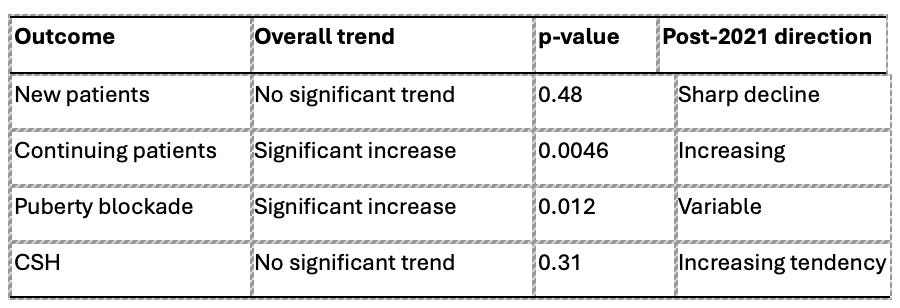

For total patients there has been a strong increase over time, from 410 in 2017 to 1,226 in 2025. New patient referrals peaked in 2021–22 and have declined for three consecutive years since 2021–22. This reduced incidence is not yet statistically significant because there are insufficient data points past the peak referral year. If we formed conclusions from the intake numbers alone, it would be difficult to argue that numbers are not declining. However, there is a difference between observed change and statistically significant trends. Currently, there is no statistically confirmed long-term downward trend in new patients. Table 2 shows the trend.

Table 2: Trend in RCH patient data

To date, there have been three consecutive years of contraction, with an overall reduction of ~65% from peak. (However, as I explain below, there has been a diversion of patients from RCH to the Orygen/headspace Trans and Gender-Diverse Health Service, which takes young people from age 12.)

The picture at RCH itself becomes more complex when other available data are analysed. These indicate that the overall activity of the RCH gender service has not declined. Numbers of patients who are continuing care have shown a statistically significant increase. This reflects longer treatment pathways and cohort accumulation.

Further, there is no downward trend in the number of children taking puberty blockers. The trend currently suggests long-term increase with expected year-to-year variability.

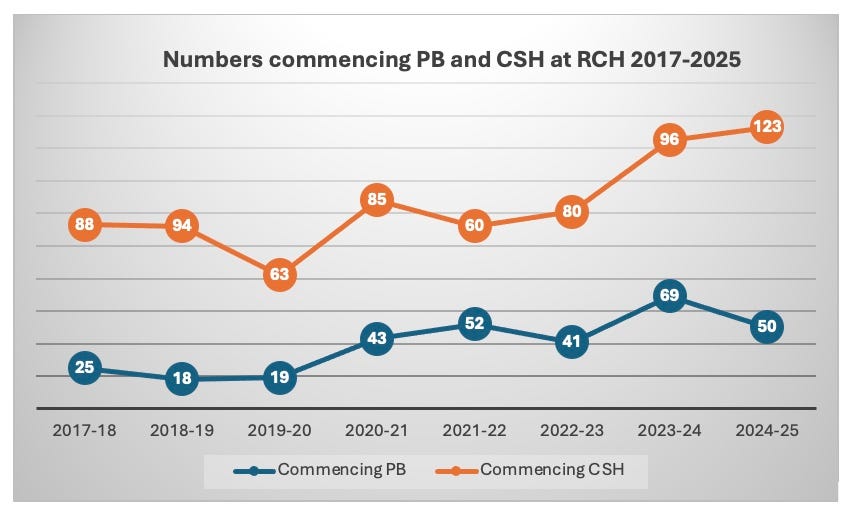

Similarly, there is no decline in the number of young people on cross-sex hormones. In fact, there have been recent increases despite fewer new referrals. Table 3 shows the trend analysis for each category of patient since 2017.

Table 3: Trend in patient categories at RCH

From these data we conclude that there is no evidence of reduced medical intervention, and no evidence of reduced service demand overall (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Hormonal interventions at RCH

It is important to note that new referral numbers and treatment numbers are not interchangeable indicators. Current short-term declines in referrals do not yet indicate reduced clinical services/intervention. Even though new referrals have declined since 2021–22, ongoing “care” and interventions (PB and CSH) continue at sustained or increasing levels. The upward trend in the prescription of CSH at RCH is disturbing given that RCH only accepts young people up to the age of 16 years. This means that this service is providing CSH to 14-15-year-olds!

Conclusion

Across the 2017–18 to 2024–25 period, total and continuing patient numbers increased significantly, while new patient referrals peaked sharply in 2021–22 and declined substantially over the subsequent three years. Although this post-2021 decline in new patients is large in magnitude, averaging −172 patients per year, it does not yet meet statistical criteria for a sustained downward trend due to the short post-peak observation window.

On the contrary, numbers commencing puberty blockade and CSH show no evidence of decline; puberty blockade commencements increased significantly over the full period, and CSH commencements display a rising tendency in recent years. The data therefore support a distinction between declining new referrals and continuing or increasing treatment initiation among existing patients.

If current post-2021 trends persist, new referrals could drop to around 50 in the year 2026-2027. However, ongoing treatment of continuing patients, growing at around 150 per year, would bring the total number treated to around 1,350 by 2026-2027. We must therefore conclude that declining new referrals do not equate to reduced service volume or reduced medical intervention.

How can we understand the sharp decline in new patient referrals to RCH?

In Victoria, Australia, in addition to the RCH gender service, several other services also offer gender interventions to young people. These include the Monash Gender Clinic, which accepts referrals from young people aged 16+ and the Orygen/headspace Trans and Gender-Diverse Health Service, which accepts young people aged 12-25 years and provides CSH. This service is available across the five Orygen-led headspace centres, as well as via telehealth. One of their stated key responsibilities is to recruit GPs into their Trans and Gender-Diverse (TGD) Health team. These GPs will then “support” other GPs and registrars to provide gender services, much in the same way as pyramid-selling schemes operate in commercial markets. In addition to Orygen/headspace, at least another seven community-based gender services operate throughout the state.

With so many service providers for TGD young people, one explanation for the decrease in RCH new referrals is that the common pool is being divided amongst more providers, with regional young people using the now-available regional services.

In 2022, Michelle Telfer, former director of the gender service at RCH, spoke of the collaboration with Orygen as a Gender Service Expansion Project, and described it as “a collaboration funded by the Victorian Government in 2021, which brings together Orygen and their five associated headspace centres in northwest metropolitan Melbourne, RCH, Monash Health, Transgender Victoria, and Transcend Australia.” Orygen has shifted its priorities from those originally stated at its inception, which were to provide services for early onset psychosis.

The role of COVID-19 in referral patterns is not clear. One would have expected a decrease, not a peak, in 2021 at the height of the pandemic, but several clinics reported peak referral numbers.1 One explanation is that COVID was highly disruptive to the development of children and young people and there was an increase in emotional and behavioural disorders. Excess social and digital media use during which transgenderism was aggressively marketed, together with social isolation, may have resulted in some young people expressing their psychological distress as a gender identity crisis.

Since then, there appears to have been a decrease in referrals to gender clinics across Australia, but this is probably an artefact of the greatly expanded gender services on offer and the incursion of private practitioners into this field, from whom numbers are very difficult to obtain.

In summary, the most likely candidate explanations for the drop in new referrals to RCH since 2021 include the Orygen/headspace project and other expansion strategies, and a reduction in the upper age limit for referrals to RCH to <16 years. The Queensland Children’s Gender Service also revised their upper age limit to <17 years, which was accompanied by a similar reduction in new referrals.

Limitations

Data on clinical referrals and treatment for trans youth in Australia are incomplete and possibly unreliable because health services do not uniformly publish comprehensive annual figures, they make it difficult to obtain figures from gender services (e.g., Orygen has refused to provide data), require lengthy freedom of information applications, and private practice activity is rarely captured.

Professor Kenny, a child and adolescent psychologist, is author of the book InTRANSigence

This is in contrast to the effects of the COVID pandemic that resulted in a decrease of referrals to adult gender services worldwide.

PREVENTING CHILD SUIICIDE - THE GENDER PHYSICIANS NAILED IT!

Suicide is the leading cause of death among Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. It accounts for around 27% of all deaths in that age group. This represent one of the starkest public health disparities in Australia, a source of national shame.

A public health crisis demands urgent appropriate human resources and unbridled funding.

There are those who believe that we have recently experienced and are solving a global public health crisis:

. . . .Gender Dysphoria spontaneously appeared out of the blue around 2010. The experts informed us that it had had nothing to do with social contagion and that without massive institutional and fiscal support children would be suiciding on-mass.

Cheques were signed, outrage raged, a new breed of gender physician hero appeared. They understood what was going on and assured parents that they need trust their judgement.

Thus far the outcome has been most impressive: Not a single suicide and all those previously distressed children joyous in their made-to-order body.

. . . . Meanwhile, for around 27% of our indigenous young things remain pretty much the same.

Does anyone know of any law firms who know the truth about gender ideology / any class actions being brought?