Public purse

Doctors urge universal taxpayer funding for trans surgery undertaken as 'a personal choice'

The gist

Almost 50,000 Australians aged 18 and older are expected to undergo transgender surgeries such as double mastectomy or the creation of an artificial vagina in the first year of a radical plan for universal public funding of “gender-affirming” medical interventions.

“The medical interventions accessed will depend on a person’s personal choice as to which medical affirmation intervention(s) are right for them,” the Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons says in its application for new Medicare item numbers to explicitly fund a full range of gender-affirming surgeries including genital procedures with high rates of complications.

In “depathologisation” mode, the proposal would make “gender incongruence of adolescence and adulthood” the criterion for access to trans surgery subsidised under the country’s Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS).

Gender incongruence is said to be a condition involving a feeling of mismatch between someone’s birth sex and their “gender identity”. It is not considered a mental illness and diagnosis does not require the person to feel any distress about the mismatch.

In its application, the plastic surgeons’ society makes the unsupported claim that gender incongruence is “innate”.

For advocates of the gender-affirming treatment approach, the term gender incongruence is increasingly preferred to the psychiatric diagnosis of gender dysphoria, which requires distress and is seen as more “pathologising” of trans and non-binary identities. (Gender dysphoria was adopted in 2013 as less pathologising than the previous condition “gender identity disorder”.)

A subcommittee of the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC), which is charged with giving Australia’s government independent advice on the merit of public funding for new medical interventions, is to discuss the request from the society of plastic surgeons at its December 7-8 meeting. A round of public consultation is open until November 3.

A psychiatrist critical of the gender-affirming model, who spoke anonymously to avoid harassment by activists, told GCN that the federal Health Department “would be within its rights to question if a condition [such as gender incongruence] causes no distress, what is the purpose of medical treatment?”

The psychiatrist, who has had experience with MSAC applications, said the committee “includes about as many economists as clinicians, underscoring the importance to the federal government that funding of health needs to be cost efficient and balanced in terms of other health priorities and the priorities of other departments.”

Although the gender clinic debate internationally has focused on the extraordinary increase in minors seeking gender medicalisation, there is emerging concern about the overlooked group of young people aged 18-25 with still developing brains.

Other reasons for this concern include the cascade of interventions, with minors begun on puberty blocker drugs likely to continue down the medical path as young adults, and the fast-tracking of older adolescents from paediatric clinic waiting lists to adult gender clinics.

Detransitioner Keira Bell, the young woman who launched an ultimately unsuccessful legal action against the world’s largest youth gender clinic, the London-based Tavistock service, started puberty blockers at age 16, but underwent mastectomy when she was 20. In Australia, detransitioner Jay Langadinos is suing the psychiatrist who cleared her for cross-sex hormones at age 19, followed by mastectomy and hysterectomy.

“We are a group of clinicians and academics concerned about the treatment of young people, aged 17-25, in [England’s] adult gender identity services. One fifth of those referred to adult services are still legally children (17), and two thirds are developmentally adolescent (17-25). There is considerable evidence that identity may not settle until the mid-twenties. Some may argue that once young people are 18, they are adults, so consent is a simple matter. We disagree. Because of the complexity and co-morbidity in such cases, the decision to place these young people on a surgical pathway should be made with caution.”—letter to The Sunday Times advising caution before referring anyone under the age of 25 for cross-sex hormones or surgery, 28 May 2023

Video: Daisy, an American detransitioner who began taking testosterone at age 18 and had ‘top surgery’ (double mastectomy) two years later, talks about transition regret and hope

The detail

‘Anxious doctors’

The Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons says the MBS schedule fees that would be payable for trans surgery have yet to be finalised. Its application lists 20 trans surgeries as already being performed. Out-of-pocket costs are said to range from $8,000 to $80,000, depending on the surgery.

The society says some of these surgeries are not funded at all under the MBS. Others get public funding, but the society says the MBS item descriptors “are a ‘poor fit’ for performing gender-affirming [surgeries] and cause anxiety to doctors using them as to whether they are using the appropriate MBS item.”

The society suggests there is “broad public support” for its funding application, citing a 2021 petition to Australia’s then health minister, Greg Hunt, with 148,182 signatures calling for Medicare coverage of gender-affirming surgery.

Responding to the petition at the time, Mr Hunt emphasised the role of MSAC to give advice on “whether a new medical service or technology should be publicly funded, based on an assessment of the comparative safety, clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness, using the best available evidence.”

Also in 2021, Australia’s minority Greens Party announced a proposal for $15 million in annual public funding for gender-affirming treatment to cover trans patients’ out-of-pocket expenses.

Earlier this year, 63,060 people signed a counter-petition arguing that Medicare should be kept for medical treatments, whereas gender affirmation was “a personal choice” that taxpayers should not have to subsidise.

“There’s a massive price tag on being transgender in Australia. For some, the cost of surgery and treatment for gender dysphoria will crack $100,000. The ABC’s new podcast The Signal has been following one woman’s effort to find the money she needs to transition, while living below the poverty line.”—news report, public broadcaster ABC, 2018

No gatekeepers?

The MSAC form requires applicants to list “all appropriate” professional bodies representing health professionals who may be affected.

The plastic surgeons’ society did not list the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, the Australian Psychological Society or any other body of mental health professionals. This exclusion is consistent with dislike of “gatekeepers” controlling access to medical treatment.

However, the surgeons’ application cites an alarming 43 per cent rate for self-reported suicide attempts among 928 trans adults (in an online survey lacking a representative sample), and argues that trans surgery helps prevent gender dysphoria in a similar way that women with a high genetic risk of breast cancer may seek a preventive mastectomy.

“Both populations have a very high risk of a severely debilitating disorder and in both cases only a subset will choose to undergo treatment and the treatment plan will vary depending on the individual needs, risk profile and choices of the patient,” the society says, while admitting the analogy “is not perfect.”

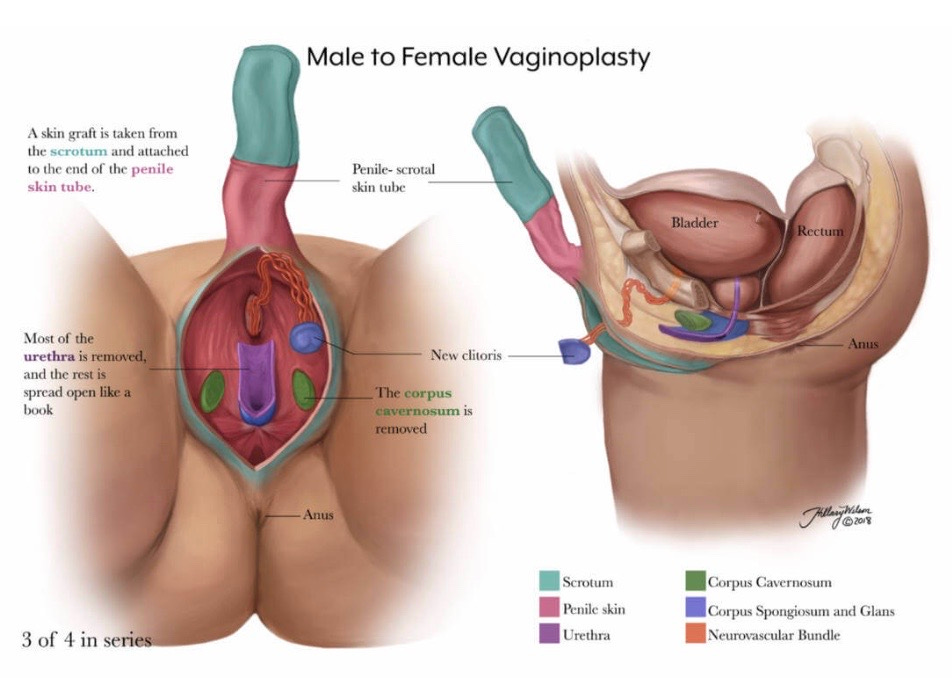

Diagram: Creation of an artificial vagina

Transition is passé

Although the World Health Organisation’s ICD-11 diagnostic description says gender incongruence “often leads to a desire to ‘transition’,” the plastic surgeons’ application says outdated talk of being “born in the wrong body” or transitioning from “male-to-female” or vice versa has been replaced with “greater recognition of non-binary and other types of gender incongruence.”

“Some individuals with a diagnosis of gender incongruence will seek limited surgical intervention, some will seek more extensive surgery, and some will seek none at all, and furthermore, the extent of treatments may not correlate with their ‘type’ of gender incongruence,” the society’s application says.

A recent trend is for young females to declare themselves “non-binary” (neither male nor female) but seek a mastectomy, blurring the familiar rationale that this surgery is necessary for female-to-male transition.

The latest, 8th edition of the standards of care issued by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) includes a new “eunuch” category of males whose “medically necessary gender-affirming care” may involve “castration to better align their bodies with their gender identity.”

The plastic surgeons’ application estimates that 128,145 transgender Australian adults (57 more males than females) would be candidates for gender-affirming medical interventions in 2023. In the first full year of the new MBS item numbers, the society says an estimated 47,087 people would avail themselves of trans surgeries.

The 2016 Census recorded only 1,260 trans people in Australia. Like the associated diagnoses, the definition of the umbrella term “trans” is subject to change against a background of rights-driven activism and reinvention of language.

There remains tension between supposedly “depathologised” trans identities and on-demand access to lifelong medicalisation. For example, the plastic surgeons’ application to the government proposes that those undergoing gender-affirming medical interventions be given access to subsidised management plans currently restricted to people with chronic disease or terminal illness.

The surgeons’ application cites WPATH’s standards of care recommendation that “healthcare systems should provide medically necessary gender-affirming health care”.

The application proposes new Medicare item numbers for the following “therapeutic procedures”—

Gender-affirming chest surgery

Feminising chest surgery, by any method, including but not limited to, insertion of prostheses, autologous fat graft or local flaps

Masculinising chest surgery without surgical repositioning of the nipple areolar complex

Masculinising chest surgery with surgical repositioning of the nipple areolar complex

Revision of masculinising or feminising chest surgery

Genital reconfiguration surgery

Penectomy and bilateral orchiectomy (feminising)

Construction of neo-vagina by any method using penoscrotal skin (feminising)

Construction of neo-vagina by skin grafting around a mould (feminising)

Construction of neo-vagina by any method using intestinal segment (feminising)

Revision of construction of neo-vagina surgery

Hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy (masculinising)

Construction of neo-phallus by any method using local flaps (masculinising)

Construction of neo-phallus by microvascular transfer of free autologous tissue (such as radial forearm flap or antero-lateral thigh flap) (masculinising)

Construction of neo-phallus by metoidioplasty (formation of penis from clitoral tissue) (masculinising)

Revision of construction of neo-phallus surgery

Gender-affirming facial procedures

Feminising/masculinising facial surgery, remodelling of forehead and orbits

Feminising/masculinising facial surgery, one or more mandibular ostectomies and mandibular reshaping if undertaken

Feminising/masculinising facial surgery, insertion of facial implants or bone grafts

Feminising/masculinising facial surgery, soft tissue surgery including skin advancement or local flaps to forehead or lips and including fat grafting

Revision of feminising/masculinising facial surgery

Gender-affirming voice surgery

Chondrolaryngoplasty for gender affirmation (feminising)

Diagram: Creation of an artificial penis

Strong evidence?

The psychiatrist with experience of MSAC applications told GCN the committee would expect “a large volume of high-quality evidence to support the efficacy of the proposed intervention for the target symptoms, as compared to all other interventions employed internationally in this field, and there should be evidence of some advantage of this intervention over other treatments.”

The society’s application cites a clutch of low-quality treatment guidelines and observational studies, one systematic review of hormone treatment which acknowledges the lack of controlled trials and the low quality of the evidence for benefit, as well as a systematic review of phalloplasty (the creation of an artificial penis) reporting a 54 per cent complication rate, which the authors of the review imply is likely to be lower than the true rate. “Satisfaction was high, although most studies did not use validated or quantified approaches to address satisfaction,” the authors say.

Noting the low-quality nature of studies in gender medicine, the psychiatrist said the plastic surgeons’ application also lacked a cost comparison analysis.

“This is really important given the MRI scan fiasco about 20 years ago, when it was feared that radiology providers would take advantage of a proposed [Medicare] item number for MRI scans,” he said.

“The MSAC has been careful to seek proof of cost advantage to the federal government when introducing new Medicare item numbers since.

“Again, you would need comparison trials [pitting gender-affirming treatment against alternatives] to show a cost advantage, and affirmation proponents refuse to countenance such trials [for ideological reasons].”

The MSAC form asks applicants how the medical service to be funded compares with existing services—whether it is “superior, non-inferior or inferior.”

The society’s application presents gender-affirming surgery as the de facto medical standard and offers no study comparing its health outcomes with non-invasive therapies.

Instead, the society declares that gender surgery with universal public funding is “non-inferior” to the current state of affairs with gender surgery having patchy public funding.

Suicide narrative

The plastic surgeons’ application says, “Gender-affirming medical interventions have been reported as reducing rates of psychological distress, suicide ideation and suicide attempt.”

It cites a low-quality study (Almazan 2021) involving a secondary analysis of the 2015 US Transgender Survey, an online survey run by a trans advocacy body and lacking a representative sample.

By contrast, Sweden’s unusually comprehensive long-term health data suggests a conclusion discouraging for advocates of trans surgery.

The 2011 Dhejne study covered all “sex-reassigned persons” in Sweden from 1973-2003. It found that trans people after surgery had a suicide rate 19 times higher than matched controls. (The study shows an association but cannot illuminate causation.)

“Mortality from suicide was strikingly high among sex-reassigned persons, also after adjustment for prior psychiatric morbidity,” the authors say. “Previous reports suggest that transsexualism is a strong risk factor for suicide, also after sex reassignment, and our long-term findings support the need for continued psychiatric follow-up for persons at risk to prevent this.”

In 2019, another long-term study using Sweden’s rich national data reported that trans surgery reduced the need for mental health treatment by 8 per cent a year over the ensuing decade.

“No longer can we say that we lack high-quality evidence of the benefits of providing gender-affirming surgeries to transgender individuals who seek them,” said the study’s co-author, Professor John Pachankis, who directs the LGBTQ Mental Health Initiative at Yale University.

Published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, this paper was widely promoted in mainstream media, with Newsweek magazine quoting unnamed “scientists who say such [surgical] interventions must be as easy as possible to access.”

However, researchers and scientists, including some advisors to the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine, alerted the journal to methodological problems in the study, leading to an independent reanalysis of the data.

In 2020, the journal published a correction, an editorial and letters from a dozen psychiatrists, clinicians and researchers in four countries identifying multiple flaws in the 2019 paper, with the ultimate conclusion that there was in fact “no advantage” for mental health after surgery. This correction was little reported in the media.

Surgery, revised

The Australian Plastic Surgeons Society acknowledges that an initial trans surgery may beget further operations, and so requests public funding for “revision” procedures following gender-affirming surgery.

The society’s application also seeks specific funding for “genital reconfiguration surgery” (known as “bottom surgery”) involving “construction of [a] neo-vagina by any method using intestinal segment.”

This is aimed at boys begun on puberty blockers around age 10-12 whose genital growth is stunted, meaning there is not enough tissue from the penis and scrotum to create an artificial vagina. Surgeons instead use a section of the bowel. This is more risky, and resulted in the death of one patient from infection in the original small-group Dutch research that inspired the international spread of paediatric gender medicine.

Asked to list the “patient and consumer advocacy organisations” relevant to its application, the plastic surgeons’ society nominates the Australian Professional Association for Trans Health and the former gay rights body ACON, both of which also function as lobbies for providers of gender-affirming medical interventions. The group Genspect, which advocates for non-medicalised responses to gender distress, is not included.

GCN sought comment from the plastic surgeons’ society

Plastics. Truly depraved in my view.

Given that gids is closing down and the model of care is being brought into accord with what the evidence does and does not say, I think Keira Bell was successful even though her suit was not won :).