On the defensive

The NZ Ministry of Health no longer claims puberty blockers are safe and reversible

The gist

New Zealand’s Ministry of Health has quietly abandoned its public claim that puberty blocker drugs are a “safe and fully reversible” medicine for children who declare a transgender identity and want to interrupt their normal sexual development.

Since mid-August, there have been two separate breakthrough articles in NZ media by emeritus professor of epidemiology Charlotte Paul and health sociologist Dr Sarah Donovan.

Professor Paul’s comprehensive article published earlier this month in the New Zealand Listener magazine highlighted international concerns about puberty blockers, treatment regret and the capacity of children to consent to this intervention.

In the online platform newsroom on August 18, Dr Donovan asked why local news outlets had failed to report landmarks in the international debate such as the decision to close the world’s largest youth gender service, the London-based Tavistock clinic.

“How does the New Zealand model of child and teen gender services compare with the [U.K. National Health Service] model now being urgently overhauled? What a great piece of local investigative journalism that would make,” Dr Donovan wrote, expressing frustration at NZ “media silence” on the global gender clinic story.

As in other countries, the hormone suppression drugs used to block puberty are not approved to treat gender dysphoria, which involves a distressing feeling of conflict between the body and an inner sense of an opposite-sex “gender identity”.

An August 1 screenshot of the NZ health ministry’s webpage headed “Transgender New Zealanders: Children and young people” included the claim: “Blockers are a safe and fully reversible medicine that may be used to help ease distress and allow time to fully explore gender health options”.

Now that sentence reads: “Puberty blockers are a medicine that can be used to halt the progress of potentially unwanted puberty-related physical changes”.

The webpage states that it was last updated on September 16. Over the last two years, more than a score of New Zealanders concerned about the safety of puberty blockers had contacted the ministry to challenge its claim, but were stonewalled.

Although the general public is no longer reassured that puberty blockers are safe and reversible, the ministry still supports that claim indirectly when advising health professionals on how to respond to gender-questioning minors.

The ministry webpage “Providing health services for transgender people” links health professionals to the 2018 Guidelines for Gender-Affirming Healthcare, which claims puberty blockers are “fully reversible” and says there is “good evidence” they improve mental health.

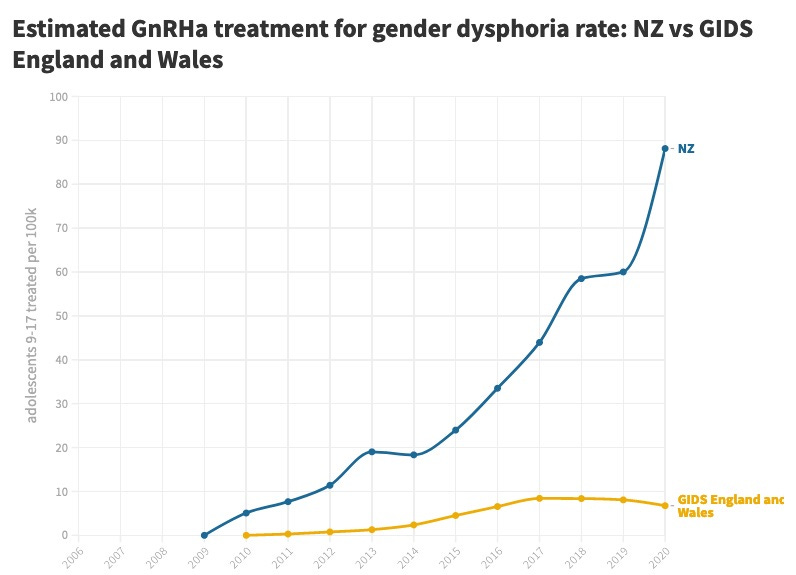

The per capita usage of puberty blockers in NZ appears to be dramatically higher than at the Tavistock clinic, according to an analysis of official figures by Simon Tegg of the group Fully Informed, which seeks to shine a spotlight on youth gender medicine.

In 2020, for every 100,000 adolescents, NZ had 88 children aged 9-17 on blockers, compared with 7 per 100,000 in England and Wales, which are served by the stand-alone specialist Tavistock clinic.

“Because the treatment rate is so high, almost everyone in polite society with high school-age children will know of a young person undergoing hormone treatment in their social circles,” Mr Tegg said.

Puberty blockers, which have been started with children as young as 10, are no longer considered routine treatment in Sweden, Finland and the UK, where systematic reviews have exposed the weak evidence base for medicalised gender change with minors.

Concerns about puberty blockers include low bone density with the risk of osteoporosis, and potential interruption to a crucial period of brain growth and psychological development with the effect of locking in a medicalised opposite-sex identity. If started early in puberty and followed by opposite-sex hormones, the result of this regimen may be sexual dysfunction and sterility as adults.

Professor Paul, who sent a 2500-word letter to NZ Health Minister Andrew Little in April 2021 expressing her concerns and seeking information, said she had asked the ministry to commission a review of puberty blocker use.

“This [review] needs to be done independently because the experts the ministry consulted have supported the status quo, and presumably rejected the need for a review,” she told GCN.

Chart: Estimated use of puberty blockers (GnRHa) per capita by adolescents in NZ and at the London-based Tavistock GIDS clinic

The detail

Breaking the silence

In her Listener article, republished by the mass market masthead NZ Herald on September 12, Professor Paul said younger colleagues had pleaded with her to write on the hot-button topic of gender medicine because they feared the consequences for their careers if they spoke out.

“My colleagues approached me because they're concerned about the rapid increase in the use of hormones to suppress normal puberty in children and young people who express discomfort with their biological sex,” she wrote.

“They're especially concerned that the grounds for accessing these hormones have widened greatly. How do we know this is doing more good than harm?

“My colleagues are seeing in their clinics young people who have changed their minds about wanting to transition away from their biological sex and who also have serious mental health problems that have been left unaddressed.

“They doubt whether there is sufficient psychological assessment for children with gender dysphoria before they are prescribed puberty blockers — to help distinguish those who will remain transgender from those for whom it is a phase.

“They also question the capacity of children to consent to the intervention. They are worried about the lack of knowledge of long-term harms and benefits.”

Before the 2010s, hormone suppression drugs (GnRH analogues) were better known for treatment of early puberty (central precocious puberty) than for gender dysphoria.

Official NZ data does not distinguish between these two different treatments, so the rise of trans puberty blockade has to be inferred from the older age of dysphoria patients.

In the 10-17 age bracket, where gender dysphoria is the likely condition being treated, there were 505 patients on puberty blockers in 2020, an increase of 66 per cent since 2017.

At the Christchurch Youth 298 health service in March last year, about 65 of the 100 “gender diverse” young people were reportedly on puberty blockers, and roughly 80 per cent of those on blockers went on to potentially lifelong opposite-sex hormones.

In her newsroom article, Dr Donovan drew attention to “some pretty extraordinary developments” in the U.K., including news of a potential class action law suit against the Tavistock youth gender clinic, the independent review of care by paediatrician Dr Hilary Cass, and NHS plans for a less medicalised, more holistic approach to care.

She described the NZ health ministry’s claim that puberty blockers were safe and fully reversible as “oddly out of step with the hesitancy being expressed internationally — hesitancy which has seen a number of internationally renowned gender medicine clinics end the use of these drugs for under 18s within the last few years”.

She noted that the NHS offered the public more cautious advice on blockers than NZ.

In 2020, the NHS abandoned without explanation its claim that blockers were “fully reversible”.

Instead, the NHS said: “Little is known about the long-term side effects of hormone or puberty blockers in children with gender dysphoria.

“Although the Gender Identity Development Service [the Tavistock clinic] advises this is a physically reversible treatment if stopped, it is not known what the psychological effects may be.

“It's also not known whether hormone blockers affect the development of the teenage brain or children's bones.”

Dr Donovan told GCN that if news media did not do their job, it was harder for families to make fully informed decisions about health care.

“The role of the media is to help people identify where there might be evidence gaps that aren't being adequately pointed out by those we trust to provide our health policy and guidance,” she said.

She had left messages for NZ journalists about the big international story of the Tavistock clinic but was “just completely ignored, not even had my emails acknowledged, which really surprised me”.

She was also surprised by the silence of social scientists on the unexplained international surge in teenagers, disproportionately female, declaring a trans identity and seeking medical interventions.

“Why is it that girls are suddenly no longer wanting to be girls — and in such numbers?,” she said.

“I'm not seeing anything [in the universities] trying to explain the phenomenon other than the apparently unquestioned narrative that all of these girls already were wanting to transition, but now they feel confident to do it.”

Video: Californian Chloe Cole explains her disillusionment with gender medicine

Off-label drugs

Although the NZ regulator Medsafe has not approved hormone suppression drugs to be used for gender dysphoria, they are fully funded by the NZ taxpayer.

These drugs internationally are licensed for other conditions including early onset of puberty (central precocious puberty), prostate cancer, and endometriosis.

In February, Dr Cass’s interim report on the care of U.K. youth with gender distress said: “It is important that it is not assumed that outcomes for, and side effects in, children treated for precocious puberty will necessarily be the same in children or young people with gender dysphoria”.

That same month, Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare declared that “the risks of puberty suppressing treatment with GnRH-analogues [hormone suppression drugs] and gender affirming hormonal treatment [opposite-sex hormone drugs] currently outweigh the possible benefits”.

In 2016, the NZ pharmaceutical funding agency Pharmac decided to make the hormone suppression drug Zoladex (chemical name: goserelin) the sole, fully funded supplier.

Documents seen by GCN suggest that Pharmac’s decision was not informed by any consideration of the harms and benefits of this drug for children with gender dysphoria.

Goserelin is “open-listed”, meaning it can be prescribed for any use if a health professional thinks it “clinically appropriate”, and discusses the risks and benefits with the patient, according to the NZ health ministry.

When asked by GCN this week, the ministry could not produce any documents showing that an analysis had been undertaken of the risks and benefits of hormone suppression drugs when used to block normal puberty.

In her Listener article, Professor Paul said she was surprised to learn that hormone suppression was not approved for use with gender dysphoria.

“In New Zealand, the Medical Council issues guidelines for unapproved medicines, or those unapproved for particular uses,” she wrote.

“Unapproved medicines must be subject to monitoring, to prior discussion with a senior colleague, and the patient must be given extra information about risks and benefits — including that the medicine was being prescribed for an unapproved indication.

“None of this (apart from monitoring height and bone density) is mentioned in the New Zealand [2018] Guidelines for Gender-Affirming Healthcare.”

Dear doctor

Family doctors and other health professionals in New Zealand’s various regions have password-protected access to HealthPathways information.

“We [as family doctors] assume that HealthPathways is up-to-date, evidence-based and approved by [medical] colleges and the Ministry of Health,” said a doctor who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“It is our first port of call with our clinical decision-making when we feel unsure or want to double-check something."

In the Southern District Health Board area, the HealthPathways material — headed “Transgender Health in Children” — presents puberty blockers as “a reversible intervention”.

“If appropriate, ensure the child understands the concepts of puberty and that referral for endocrinology discussion [about puberty blockers] will occur when they are aged 8 years or older,” the HealthPathways webpage says.

“If [puberty blockers are] discontinued, the young person will go through endogenous puberty (including retained ability to ovulate or produce sperm) after six months.”

However, this is “almost a moot point” because the limited data available show that the vast majority of children started on puberty blockers go on to opposite-sex hormones with irreversible effects on the body, according to endocrinologist Dr William Malone of the Society for Evidence-based Gender Medicine.

“The two [hormonal treatments] shouldn’t be discussed by medics as separate entities — they’re really a package,” Dr Malone told GCN.

“Talking about puberty blockers as reversible in theory, but not in practice, minimises the momentous step that starting puberty blockers represents.”

The HealthPathways advice does acknowledge that “many children” with gender dysphoria will no longer have it by the time they reach adolescence or adulthood.

It also says that mental health conditions should be “moderately or well controlled” before puberty blockers are given.

The Southern DHB HealthPathways material on “Transgender Health in Adolescence” reveals a lowering of safety standards for “genital reconstruction surgery” — the removal of reproductive organs, known in the trans community as “bottom surgery”. These procedures can involve significant medical complications.

“For genital reconstruction surgery, national and international guidelines state that two psychological assessments are required for genital reassignment surgery,” the webpage says.

“However, currently, as the waiting list [for mental health assessments] is long, only one assessment is required.

“If a patient has already had a psychological assessment before starting hormone treatment or other gender-affirming surgeries, this assessment is sufficient for them to be added to the gender reconstruction waiting list.”

In the same context of trans health for adolescents, the webpage says the opposition of parents may not be an obstacle to medical treatment.

“Some transgender young people may not have the support of their parents or guardians, but this should not preclude them from receiving support and care,” the webpage says.

“The legal age of consent is 16 years old. The law assumes that those aged 16 years or older are competent to make their own decisions about their medical treatment.

“Patients aged younger than 16 years old can consent to their own medical treatment in the context of sexual health and contraceptive advice, and abortion.

“A minor may be legally competent to consent if he or she has sufficient understanding and intelligence to understand fully what is proposed.”

GCN sought comment from New Zealand’s Professional Association for Transgender Health Aotearoa, which endorses the 2018 gender-affirming health guidelines. The NZ health ministry was asked about the abandonment of its puberty blocker claim, and the reduced mental health safeguard for genital surgery.

Bernard,

I don't know what parents are being told however if you look at the website they state 'reversable'.

It would not seem appropriate to make such statement in the light of current knowledge:

https://www.rch.org.au/adolescent-medicine/gender-service/

Rgds

Vincent

Wow - what an excellent, thorough, and well-deserved take-down of the state of gender identity ideology around children here in New Zealand! Thanks, Bernard.