Not robust

Another gender clinician admits the scarcity of good evidence

Not good enough

An Australian psychiatrist featured in a TV program showcasing puberty blockers for non-binary teenagers has acknowledged to colleagues that the evidence for “gender-affirming” treatment is not robust.

At a psychiatry conference on October 14 Dr Georgie Swift, who was involved in setting up the gender clinic at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital (WCH) in Adelaide, South Australia, gave a talk titled, “We’re here, we’re queer and we’d like to say hello: the mental health and wellbeing of gender-diverse and same-sex attracted people.”

“I’m reasonably confident to say that no matter where you stand on gender-affirming health care for children and adolescents, that you agree that we need more evidence— our evidence isn’t robust, it isn’t good enough,” Dr Swift told the conference.

She noted that longitudinal studies had begun in gender clinics at state children’s hospital in Melbourne and Perth but said the results were years away. Like counterparts in other states, those clinics follow the gender-affirming treatment model and administer puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones.

Health authorities in Finland, Sweden, England and Florida have adopted more cautious policies restricting hormonal treatments for minors following systematic reviews showing the evidence base to be weak and uncertain. There have been steps towards greater caution in Norway and Denmark, although those two countries have not undertaken a systematic review.

“These individuals [including US physician Dr Jason Rafferty, author of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) 2018 ‘gender affirmation-only’ policy statement] saw an opportunity to pioneer new guidance on an emerging field in pediatric medicine—the treatment of the rapidly increasing number of children and adolescents presenting as transgender and gender diverse—that would enshrine as authoritative their ideological beliefs.

“But finding no evidentiary support for their radical positions, they nonetheless prepared and authored a policy statement reviewed, approved, and published by Defendant AAP, proposing an entirely new model of treatment, which not only misrepresented or misleadingly presented its purported evidentiary support but was also rife with outright fraudulent representations.”—potentially landmark litigation by detransitioner Isabelle M Ayala against the AAP and others, October 2023

Video: The post-Tavistock reforms planned by Britain’s independent reviewer Dr Hilary Cass must reckon with entrenched gender ideology

Out of sync

Puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones remain routine treatments in Australia, although Dr Swift is the second prominent gender clinician to admit—to an audience of professional colleagues, rather than the general public—that the evidence is weak.

On July 23, the founder of the gender clinic at the Queensland Children’s Hospital, Dr Stephen Stathis, told a psychiatry conference that the evidence base was of low quality and that he no longer believed the familiar claim that puberty blockers offered children a “pause” that allowed them to weigh the decision whether to proceed to lifelong cross-sex hormones.

The available data shows that the vast majority of patients begun on puberty blockers proceed to cross-sex hormones, meaning that children as young as age 10-12 are embarking upon a lifelong medical pathway which may render them sterile and unable to achieve sexual pleasure as adults.

Dr Stathis featured in the July 10 ABC Four Corners program “Blocked”, telling the audience that the evidence base is “emerging, and it’s changing.”

“And so, we’re constantly reviewing that evidence base and adapting our model of care to take into consideration the new evidence,” he said.

He did not reply when GCN emailed him to ask whether he had told the ABC team that he acknowledged the evidence base was of low quality and that he had abandoned the rationale that puberty blockers gave children time to think.

The ABC program did not mention the systematic evidence reviews, although it did note the proposal by England’s National Health Service to restrict puberty blockers to clinical trials “because there is not enough evidence to support their safety or clinical effectiveness as a routinely available treatment.”

Dr Swift and her Adelaide clinic appeared in the March 2020 ABC Four Corners TV program “Not a boy, not a girl”. The psychiatrist explained to the camera that puberty blockers were given to ease the distress of gender dysphoria and afforded the child “the time to continue to grow up a bit.”

The program did not discuss the quality of the evidence base for blockers, although Dr Swift was quoted as claiming that—

“Not allowing someone to socially transition or to medically transition, not supporting them in their gender identity is a high, high chance of them having significant mental health problems including high rates of deliberate self-harm, high rates of suicidality and suicide attempts.”

Screenshot: ‘The assessment of a young person who’s non-binary is extremely rigorous’—Dr Georgie Swift fronts Four Corners

The science

On the night the public broadcaster’s program went to air, its executive producer, Sally Neighbour, tweeted—

“If you’re interested in the science, this landmark study by the American Academy of Paediatrics [AAP] found that ‘pubertal suppression for transgender adolescents is associated with favorable mental health outcomes’.”

That study, authored by activist American psychiatrist Dr Jack Turban and others, appeared in Pediatrics, the official journal of the AAP (which recently gave in to pressure to commission a systematic review of the evidence base for paediatric transition following an unrebutted critique of its 2018 affirmation-only position statement.)

The 2020 Turban et al paper—based on a low-quality non-representative sample from an online survey that offered cash for participation—has been the subject of several rebuttals, pointing out its flaws, but Pediatrics has refused to correct the paper or publish any letters of rebuttal, according to paediatrician Dr Julia Mason, who is a founding board member of the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine.

Dr Turban’s papers, often given positive coverage in US media amid the polarised politics of gender clinics, have equally often been criticised for methodological problems and unfounded claims, albeit without any mainstream media attention.

“[Dr Jason] Rafferty’s clinical notes show that he saw [the now detransitioned plaintiff Layton Ulery] as a ‘high-risk’ patient, citing the emotional and sexual abuse she had suffered and the precarity of her current situation with no income and not enough food to eat. Rafferty then specified that ‘current goals’ of treatment included ‘masculinising hormones’ and ‘top surgery’ but that the patient was experiencing ‘internal turmoil between alters about [the] meaning of gender identity that likely requires additional support and exploration’. Yet apparently Rafferty saw nothing serious enough to delay the administration of testosterone injections.”—opinion article on litigation brought by Ulery against Dr Rafferty, who authored the AAP’s 2018 affirmation-only statement, Eliza Mondegreen, Unherd, 23 October 2023

So much we don’t know

In her October 14 talk to the conference of the faculty of adult psychiatry of the Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, Dr Swift spoke of the unknowns of gender medicine.

“There’s so much we still don’t know about improvement in [medicalised gender] transition and its impact of quality of life and mental health,” she said.

“While we’re waiting for more evidence—which is sorely, sorely needed—what do I do when meeting in a room with a child, adolescent or young adult [patient] and family?”

Dr Swift’s answer—“Clinically, when you’re seeing hundreds of patients, we base our treatment decisions around clinical experience.”

She said she believed there was enough evidence that gender-affirming interventions brought benefits to some patients. She did not reply when GCN asked how she could identify at the outset those patients who would see improvement.

A spokeswoman from South Australia’s Women and Children’s Health Network said the hospital had “a multidisciplinary team including nursing, allied health, child and adolescent psychiatrists and paediatricians supporting young people accessing the gender diversity service.

“Our specialist multidisciplinary team work collaboratively with the family, carers, and young person to ensure that decisions about treatment support the young person’s needs,” she told GCN.

She said the gender service, where Dr Swift works, followed the gender-affirming treatment guideline issued in 2018 by the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne (RCH) and promoted as “Australian standards of care.”

In its peer-reviewed form, that treatment guideline makes the claim that, “The scarcity of high-quality published evidence on the topic prohibited the assessment of level (and quality) of evidence for these recommendations.”

“[That claim] is enough for me to say this is not a trustworthy guideline”, Professor Gordon Guyatt, a pioneer of the evidence-based medicine movement and a key figure in the development of the GRADE system for rating evidence quality, told GCN.

The RCH guideline tells clinicians that depression, anxiety or psychosis “should not necessarily prevent medical transition in adolescents with gender dysphoria”, although these mental health disorders might make for more complicated treatment decisions.

The new “Statewide Gender Diversity Model of Care” for South Australia, issued by the government department SA Health, adopts the gender-affirming treatment approach without any discussion of alternatives.

The model of care document appears to say that “gender-questioning” minors who do not suffer the distress of gender dysphoria may nonetheless access treatment, which is characterised as “service provision.”

The document estimates that each year 57-161 children aged 6-10 would seek “medical therapies”, with potentially 398-1130 children aged 11-15 also requesting medicalisation. The estimate for the number of 18-24 year-olds wanting “surgical gender affirmation” is 108-545. The basis for these estimates appears uncertain.

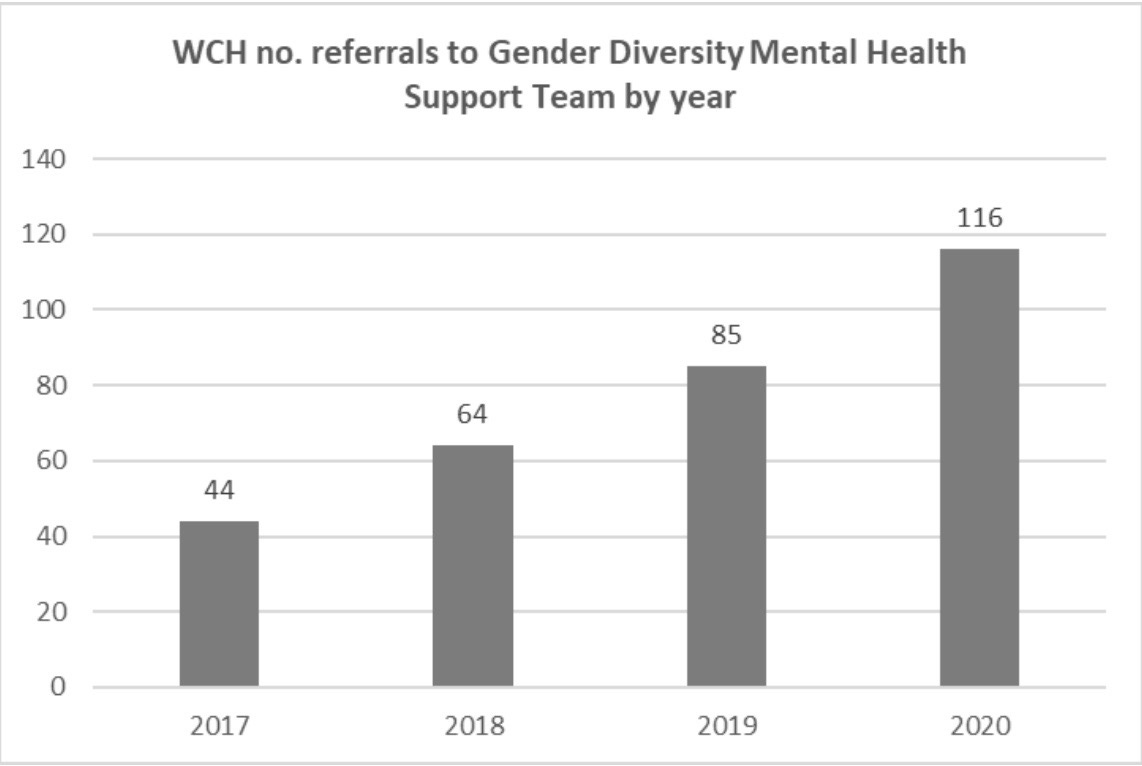

Referrals to the gender clinic at the Women and Children’s Hospital (WCH) in Adelaide rose 164 per cent from 44 in 2017 to 116 in 2020.

Graph: Rising referrals to Adelaide’s gender clinic

The model of care explicitly caters for surgery on minors—

“In cases where surgical affirmation is clinically indicated for the young person prior to transition to adult services (e.g., for young people under 18 years), referral may be made to the adult service for surgical assessment, and care provided in liaison with the adult service.”

The section for adults sets targets for “timely access” to trans surgery such as mastectomy and genital reconstruction, which has a high rate of complications.

Under the heading “Evidence-based approach”, the model of care for children and adolescents cites treatment guidelines from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and the Endocrine Society, with no hint that both were found to be flawed and not evidence-based by a British Medical Journal investigation earlier this year. The contentious RCH treatment guideline is also cited.

Also name-checked is the 2021 gender dysphoria position statement of the Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists [RANZCP].

However, the model of care document does not reveal that the RANZCP statement warns that, “evidence and professional opinion is divided as to whether an affirmative approach should be taken in relation to treatment of transgender children or whether other approaches are more appropriate.”

The model of care document, issued by SA Health, gives no sense of the shift away from gender-affirming medicalisation in Europe following systematic reviews. It offers only the opaque remark that—

“Internationally, models of care for delivery of gender diversity health services are in different stages of establishment, evaluation and/or change based on emerging research and review findings.”

A lone footnote mentions the 2022 interim report from British paediatrician Dr Hilary Cass, who was appointed by England’s National Health Service to lead an independent review of youth dysphoria care following the scandal at the London-based Tavistock clinic.

That interim report notes the lack of safety data for puberty blockers, uncertainty about their rationale and concern about their effects on the adolescent brain. For these reasons, NHS England proposes to restrict puberty blockers to clinical trials, reflecting their experimental nature.

By contrast, the SA Health document presents puberty blockers as unremarkable routine treatment, with “monitoring of bone health” the only concession to possible harms.

“Boston Children’s Hospital director calls for drastic increase in capacity for gender surgeries for minors [and says] medical school students should learn transgender surgeries in residency programs.”—news report, Hannah Grossman, Fox News, 2 April 2023

Not unusual

Like her gender clinician colleague from Queensland, Dr Stathis, whose work she acknowledged in her conference talk, Dr Swift suggested that operating with low-quality evidence was not unusual in child psychiatry.

“In psychiatry, we did lots of things that don’t have robust, excellent evidence,” she said, giving the example of prescribing for children and adolescents anti-depressant drugs better researched in adults.

She said it was difficult to engage young patients and families in conversation about the effect on fertility of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones—“It’s such a tough decision to ask people to make.”

“But I have, we all have, a responsibility to raise this [consequence of infertility] in terms of making an informed decision about what they’re doing,” she said.

Puberty blockers are started as young as age 10-12. On the available data, the vast majority of children who start on blockers go on to cross-sex hormones supposed to be taken lifelong. The combination of early puberty blockade and cross-sex hormones is expected to sterilise minors and impair their sexual function.

“I think probably 90 per cent of young people having this conversation say, ‘I’ll just adopt’,” Dr Swift said.

“As you’re probably aware… adoption in Australia doesn’t happen very often. And it’s not very realistic [as an expectation].”

She said gender-affirming hormones, like transgender surgery, were “not the panacea for mental health struggles.”

She said it was important that young patients and their families “have realistic expectations of what [the cross-sex hormones] oestrogen or testosterone or surgery can or can’t do.”

“People get a whole lot of improvements—in my clinical experience—in mental health and wellbeing, but if someone’s got a significant social anxiety disorder or major depression, [medicalised gender change is] not going to fix it,” she said.

GCN does not deny that gender-affirming clinicians may genuinely believe that their interventions benefit vulnerable children.

In 1935 the Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz pioneered the surgical procedure known as the frontal lobotomy for the treatment of serious mental health disorders. The procedure severed the nerve fibres in the frontal lobe of the brain that connected other regions of the brain.

In 1949 Moniz was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his for his breakthrough procedure.

Some 60,000 such procedures were performed in the US alone, the last in occurring in 1967 when the dreadful consequences of the procedure demanded its withdrawal.

The fact that Moniz and his followers were highly qualified and well intentioned did not prevent them from perpetrating one of the greatest mistakes of modern medicine.

There will never be robust evidence in support of gender-affirming treatment since the entire premise is built on the lie that humans can change sex. Evidence cobbled together therefore will also be built on lies. There is no metal illness or distress that can be cured by genital mutilation or sterilization.