Cognitive challenge

Research into puberty blockers and the teenage brain appears to be an afterthought

The failure of gender clinic researchers to properly investigate obvious questions about the potentially damaging effect of puberty blockers on the brain means that minors cannot be supplied with the answers they need in order to give informed consent to this treatment, according to a new paper by British neuropsychologist Sallie Baxendale.

“Vague hints from poor quality studies are insufficient to allow people considering these [hormone suppression] treatments to make an informed decision regarding the possible impact on their neuropsychological function,” says her review paper published last week on the Authorea preprint website.

“Critical questions remain unanswered regarding the nature, extent and permanence of any arrested development of cognitive function that may be associated with pharmacological blocking of puberty.

“If cognitive development ‘catches up’ following the discontinuation of puberty suppression, how long does this take and is the recovery complete?”

Puberty blocker drugs—gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues that suppress natural sex hormones—are used “off label” with children as young as ages 9-12 who do not identify with their birth sex and wish to prevent the sexual development of an unwanted puberty.

Puberty blockers have been promoted as a low-risk, no-regrets option for children (although data suggests the vast majority will go on to cross-sex hormones, which are supposed to be taken lifelong).

Marketing: America’s birth-control organisation Planned Parenthood has morphed into a major promoter of “gender-affirming care”

“Although the legal system assigns the arbitrary age of 18 years to the onset of adulthood, sophisticated neuroimaging studies demonstrate that the human brain doesn’t actually stop developing until we reach our mid-twenties… The last abilities to fully develop within the human brain are our ‘executive functions’; these are complex and include self-restraint, emotional control, the ability to appreciate nuance, the ability to plan, prioritise and strategise to achieve long term goals and the ability to weigh up information to make decisions.”—Professor Sallie Baxendale, article, Transgender Trend

Closing windows

Professor Baxendale, who holds a chair in clinical neuropsychology at University College London, says the sex hormones oestrogen and testosterone may be needed as correctly timed inputs for “critical windows” of neuropsychological development. Evidence from studies of non-human mammals suggests the impact of hormone suppression on brain structure and cognitive functions may be different for males and females. (Trans rights activists are pushing for self-identified gender to overwrite biological sex in medical data.)

In her paper, Professor Baxendale argues that research is “urgently needed” about the effects of puberty blockers on cognitive development in domains such as executive function to do with decision-making, intelligence, learning, memory and emotional processing.

“Whilst there is some evidence that indicates pubertal suppression may impact cognitive function [such as intelligence measured by IQ], there is no evidence to date to support the oft-cited assertion that the effects of puberty blockers are fully reversible. Indeed, the only study to date that has addressed this in sheep, suggests that this is not the case.”

Professor Baxendale stresses the importance of gender clinics taking baseline measures of cognitive function before giving puberty blockers.

Conditions impairing cognitive function—such as autism, AD/HD and psychiatric disorders—are over-represented in young patients experiencing the distress of gender dysphoria, so that hormone suppression may compound existing impairment.

“The impact of blocking puberty in a brain that may already be developing in an atypical trajectory is unknown,” Professor Baxendale says.

She urges gender clinics to augment their multidisciplinary teams with a clinical neuropsychologist to monitor any cognitive setbacks and help the team respond accordingly.

She suggests that neglect of the puberty blocker topic in neuropsychological research may relate to the history of hormonal suppression as an off-label treatment for gender dysphoria—these drugs have regulatory approval for hormone-dependent cancer and precocious (premature) puberty—and the reluctance of academics to enter the field because of its “highly polarised socio-political atmosphere.”

“Researchers have begun to explore the impact of context on decision making in teenagers, particularly when they are in a state of heightened arousal or excitement, and in situations involving their peers. Studies have shown that in exciting situations where consequences are immediate and direct, adolescents are less influenced by their explicit knowledge of the probabilities of potential negative outcomes, and are more willing to take risks to obtain potential rewards.”—Professor Sallie Baxendale, article, Transgender Trend

Policymakers, be warned

Professor Baxendale presented a summary of her preprint paper at the October 2023 New York conference of the Society for Evidence-based Gender Medicine (SEGM).

Also attending was the German child and adolescent psychiatrist Dr Alexander Korte, of Munich’s Ludwig-Maximilian University, who has treated adolescents with gender dysphoria for two decades.

“I am 100 per cent behind the points of criticism she formulated and the recommendations derived from them,” Dr Korte told GCN this week.

“I have held the position for years that the use of [puberty blocker drugs] in under-age patients with gender dysphoria is not ethically justifiable due to the lack of scientific evidence of the benefits of such treatment and the growing evidence of serious adverse side effects and negative long-term effects,” he said.

He said he believed the Baxendale review paper was “highly relevant” for health authorities and medical societies, such as the German Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (DGKJPP), which has been presiding over the creation of new medical guidelines for dysphoric minors in that country.

Dr Korte is himself a member of the guideline development panel but said the board of the DGKJPP had unfortunately failed to heed his warning against the “trans-affirmative” direction of the document.

“There is, however, an increasingly large group of specialists—especially university professors and clinic directors—who fully share my view and criticism of the trans-affirmative approach and early hormonal transition,” he told GCN.

Video: Professor Sallie Baxendale on puberty blockers and the teenage brain

Reversible, really?

The Baxendale paper says “there is no evidence that cognitive effects are fully reversible following discontinuation of treatment.”

“No human studies have systematically explored the impact of these treatments on neuropsychological function with an adequate baseline and follow up. However, there is some evidence of a detrimental impact of pubertal suppression on IQ.

“Despite the broad and multidisciplinary knowledge base which indicates [suppression of sex hormones] is likely to have an impact on cognitive function, and explicit calls in the literature for this to be studied that date back [to Galatzer et al’s 1984 study on precocious puberty], there have been no human studies to date that have systematically explored the impact of these [puberty blocker] treatments on neuropsychological function with an adequate baseline and follow up.”

In a key 2006 paper from the famous Amsterdam gender clinic, whose “Dutch protocol” for treatment of “juvenile transsexuals” has led to an international surge in the use of puberty blockers in children with gender dysphoria, the authors said—

“It is not clear yet how pubertal suppression will influence brain development. From our experience with adolescents, who have been taking [puberty blockers] and are now adults, no gross effects on their functioning are detectable. However, a study on brain development of adolescent transsexuals, who have used [puberty blockers], will be carried out to detect eventual subtle functional and structural effects.” (It appears this study was never undertaken.)

Yet the authors of that 2006 paper, endocrinologist Dr Henriette Delemarre-van de Waal and clinical psychologist Dr Peggy Cohen-Kettenis, made a confident claim since repeated by gender clinicians and activists around the world—that a “fully reversible treatment can be achieved using [puberty blockers]”, unlike cross-sex hormones which have irreversible effects.

Their paper declared “financial support” from Ferring Pharmaceuticals, which makes puberty blocker drugs, but Dr Cohen-Kettenis maintains the funding did not influence their research. “In case of any signs of negative effects [from blockers] we would have ended the protocol,” she told GCN.

A pivotal 2014 paper (de Vries et al, 2014) from the Amsterdam clinic tracking a small group of carefully screened patients declared success for the “Dutch protocol” of puberty blockers followed by cross-sex hormones and surgery. The protocol “provided these formerly gender-dysphoric youth the opportunity to develop into well-functioning young adults,” the paper says.

Asked if the Amsterdam clinic had an obligation to study the effects of puberty blockers on the brain, Professor Baxendale said—

“The importance of puberty as a critical neurodevelopmental stage is well established and is supported by findings from animal, clinical and imaging literature. Any injury or treatment that interrupts this process would be expected to have an impact on neurodevelopment. Presumably the Dutch group were aware of this and that is why they formally assessed everyone’s IQ before they started treatment. You will have to ask them why they did not assess the outcome using the same measure but chose to report a weak, dichotomised proxy for cognitive ability instead.”

A 2022 follow-up paper (Arnoldussen et al) on the Dutch patient group given puberty blockers reported the “reassuring” result that “gender-affirming medical treatment including [puberty suppression] does not seem to negatively affect the association between IQ and educational achievement.”

However, the authors acknowledged the need for further studies with a longer follow-up “including more frequent measurements of IQ and examining effects on executive and neurocognitive functioning.”

They split their educational outcome measure into two streams (vocational and higher vocational) in line with the Dutch school system. This was the weak dichotomised proxy for cognitive ability referred to by Professor Baxendale. Post-treatment IQ was not reported.

Of the 119 adolescents eligible for the study, only 60 per cent (72) took part.

“With [that weak outcome measure and] a loss to follow-up of around 40 per cent—and the fact that these children didn’t just have puberty blockers; many went through the whole gender reassignment program—this paper tells us nothing about the impact of puberty blockers on cognitive development,” she said.

Leading Dutch gender clinician Dr Annelou de Vries, an author of the 2022 paper and other key publications from the Amsterdam clinic, told GCN she agreed that the educational achievement measure was not an ideal proxy for cognitive ability and that it might have been a good idea to test the patients’ IQ after treatment, thereby allowing a comparison with the baseline result.

However, she said this would have been difficult to manage because the patients were not invited for a formal psychological assessment after treatment.

“It would have been costly and time-consuming and difficult to get people to participate,” she said.

Instead, the Dutch research team had used the educational achievement measure which had already been collected.

Dr de Vries said a proper study of the effect of puberty blockers on neuropsychological development would require a large number of patients with control groups and long-term follow-up.

It would also require specific measurements in expected areas of neuropsychological functioning that might be affected by puberty blocker treatment—and IQ, like educational achievement, might not be the ideal choice for such outcome measures, she said.

She said it was difficult to secure funding grants for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of the brain.

“We were planning to do such MRI studies, but we were not given the grants,” Dr de Vries said.

(This article was updated on January 15 with comments from Dr de Vries.)

Video: The brain study that never happened—coverage by the Dutch investigative journalism program Zembla

Scarce evidence

Professor Baxendale’s review of the scientific literature identified relevant studies of puberty suppression in 17 species of animals, with most of this research involving the same flock of sheep using twin controls.

“The results from these studies indicate that treatment with [puberty blocker drugs] has a detrimental impact on learning and the development of social behaviours and responses to stress in mammals,” she says in her paper.

“The results from these studies are broadly consistent and indicate that the suppression of puberty impacts brain structure and the development of social and cognitive functions in mammals, but the impacts are complex and often sex specific, consistent with the [magnetic resonance imaging] evidence of sex-specific differences in neurodevelopment in human adolescence.

“There is no evidence in the animal literature that these effects are reversible following discontinuation of treatment.”

Professor Baxendale’s literature search found “just five studies” on neuropsychological function following hormonal suppression in young people; two dealt with the condition of precocious or premature puberty and three involved gender dysphoria patients.

Only one human study (Mul et al, 2001), involving a group of 25 girls treated for precocious puberty, had baseline measures allowing inferences to be made about the effect of this treatment. After three years, the group showed a decline in IQ, which the researchers dismissed as not large enough to be “clinically relevant”.

However, Professor Baxendale says: “Whilst the average loss of IQ points was seven, it is noteworthy that at least one patient in this study experienced a significant loss of 15 points or more, since the highest IQ score in the group was 138 at baseline and this dropped to 123 following treatment.”

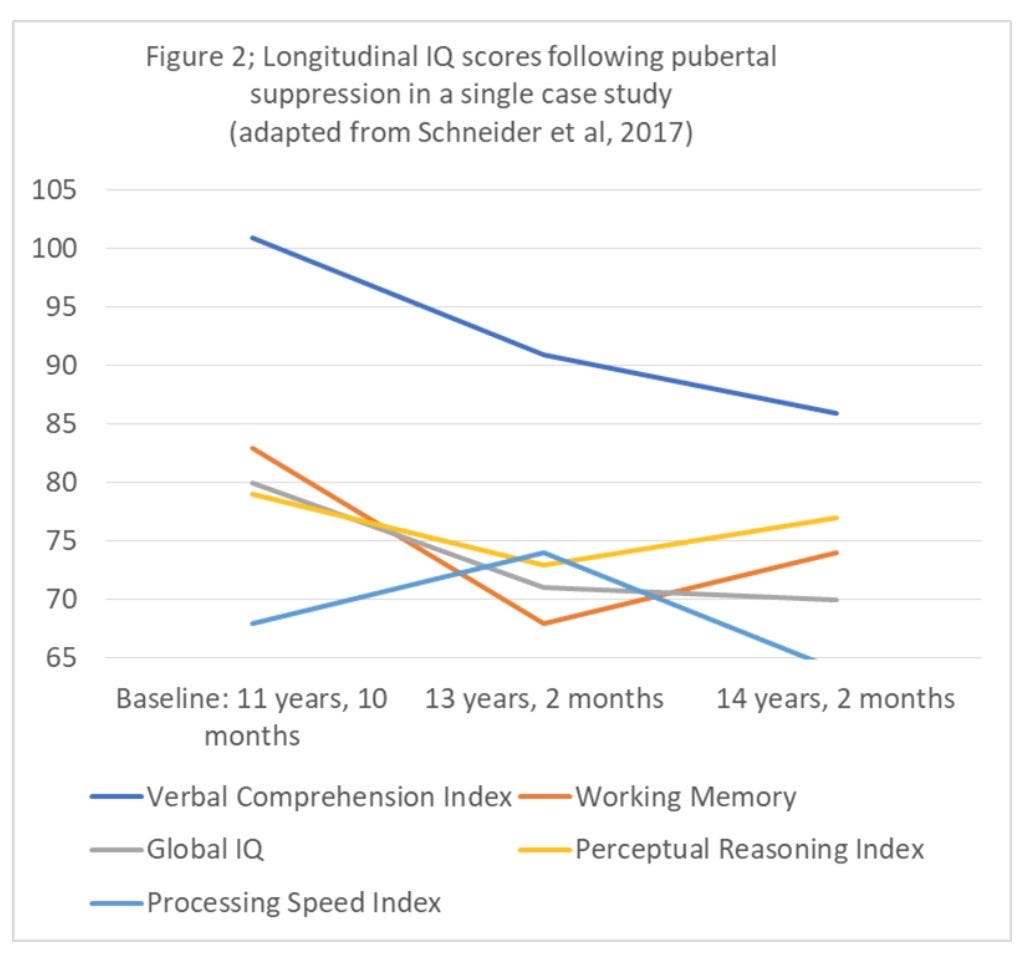

In a single case study (Schneider at al, 2017), a male patient with an IQ of 80 at just under 12 years of age showed a loss of nine IQ points when retested at 13 years and three months.

“The verbal comprehension index—a measure which depends on the expansion of vocabulary and conceptual thinking in adolescence, for the standardised score to remain stable—deteriorated progressively over the follow up, falling from the initial baseline of 101, to 91 (age 13) and 86 (age 14), a loss of 15 points over three years,” Professor Baxendale says.

Chart: Declining IQ reported in a single case study

London calling

Another study in Professor Baxendale’s review compared the performance of treated and untreated adolescents on the Tower of London Test used to measure the executive function ability to plan.

“Whilst the groups did not differ with respect to reaction time on the Tower of London Test, [hormone] suppressed male-to-females had significantly lower accuracy scores compared to the control groups,” Professor Baxendale’s paper says.

“This pattern remained significant after controlling for IQ. Despite this, the reaction-time finding has subsequently been reported as evidence for no detrimental effects on performance in citations in the subsequent literature and in policy documents.”

Two other studies reviewed by Professor Baxendale reported that before any treatment with puberty blockers, patients with gender distress performed more poorly on cognitive measures than non-gender controls. These findings reinforce the need to take baseline cognitive measures before puberty suppression, she says.

It is interesting to note that despite the widespread debate as to the unknown long-term effects of puberty suppression in children and young people that the Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital Gender Service website makes no reference to this.

I quote the relevant statement from that website:

Puberty suppression

Puberty blockers suppress the development of secondary sex characteristics and are used for adolescents in the early stages of pubertal development. As they are reversible in their effects, should an adolescent wish to stop taking them at any time, their biological puberty will resume.

The implication being that there is obviously nothing to be concerned about in relation to a little puberty suppression!

Perhaps Professor Baxendale’s attempts to bring some evidence based clarity (to acknowledge the inappropriate use of puberty suppression in minors with conditions other than precocious puberty and some specific malignancy ) might be more successful than West Sydney paediatric Professor John Whitehall’s attempts. He was siting the same veterinary research some eight years ago. His identical specifically expressed concerns of puberty suppression were not met with other than silence, or even , easily some derision, perhaps because he aligned with, shock horror, a Christian pastoral background. He wrote numerous scholarly articles in Quadrant magazine from 2016 and did his best to raise awareness for the potential for neurological and/or cognitive impairment. So, just quietly Bernard, don’t let it slip if you happen to be a man of faith! There might be more than merely the press council’s response. We all value your ongoing contributions, even if The Australian newspaper thought otherwise