The gist

Australia’s largest professional body for psychologists has begun a high-stakes review of its contentious “affirmation-only” policy for clinical work with transgender people.

The Australian Psychological Society (APS), which claims more than 24,000 members, sought nominations late last year for a review panel with a wide remit to help “shape assessment, support and therapeutic approaches for transgender and gender diverse people”.

The “affirmative” model, developed by American gender clinicians, puts its faith in a client’s self-declared “gender identity” regardless of birth sex, and endorses early social transition for children as well as medicalised gender change for adolescents.

The panel for the APS review of its “gender-affirming” policy was finalised earlier this year after lengthy delays amid a contested appointment process, and it may take up to two years before the Society issues new guidelines, GCN understands.

APS members have not been told the names of the panelists, nor the terms of reference (although the review is expected to give special attention to children and adolescents). Questioning or criticism of the politicised gender-affirming worldview can generate activist pushback and career-damaging complaints.

In September last year, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) adopted a more cautious transgender policy, earning the college a rebuke from the affirmative lobby the Australian Professional Association for Trans Health (AusPATH), which recently condemned “exploratory therapy” as often a “euphemism” for unethical attempts to force a change in gender identity so it aligns with birth sex.

The origins of the APS review predate the shift in psychiatry, GCN understands, but psychologists opposed to an affirmation-only approach have taken heart from the RANZCP’s new position, which notes the existence of “multiple perspectives and views” on youth gender issues and the “paucity” of good quality evidence on treatment.

Under the affirmative approach, some clinicians accept trans self-identification even by preschool children, and stress the “autonomy” of teenagers to access hormonal treatment and surgery without unnecessary “gatekeeping”.

The more mainstream rationale for treatment has been to alleviate gender dysphoria — the feeling of distressing conflict between birth sex and an inner “gender identity” — but some affirmative advocates regard any need for diagnosis as “pathologising” of trans people, and agitate for treatment on demand without mental health assessment from the age of 16.

Psychologists who spoke to GCN on condition of anonymity said they viewed the APS affirmation-only policy as an evidence-lite ideology running counter to established clinical practices of the profession, including comprehensive assessment and differential diagnosis.

They said the wider appeal of the policy — devised by a small group of “no debate” affirmative advocates — rested on a false parallel between fixed sexual orientation and a self-declared gender identity that potentially demands lifelong medicalisation.

Until recently, the APS leadership had not realised the extent or gravity of the international debate about youth gender medicine, GCN understands.

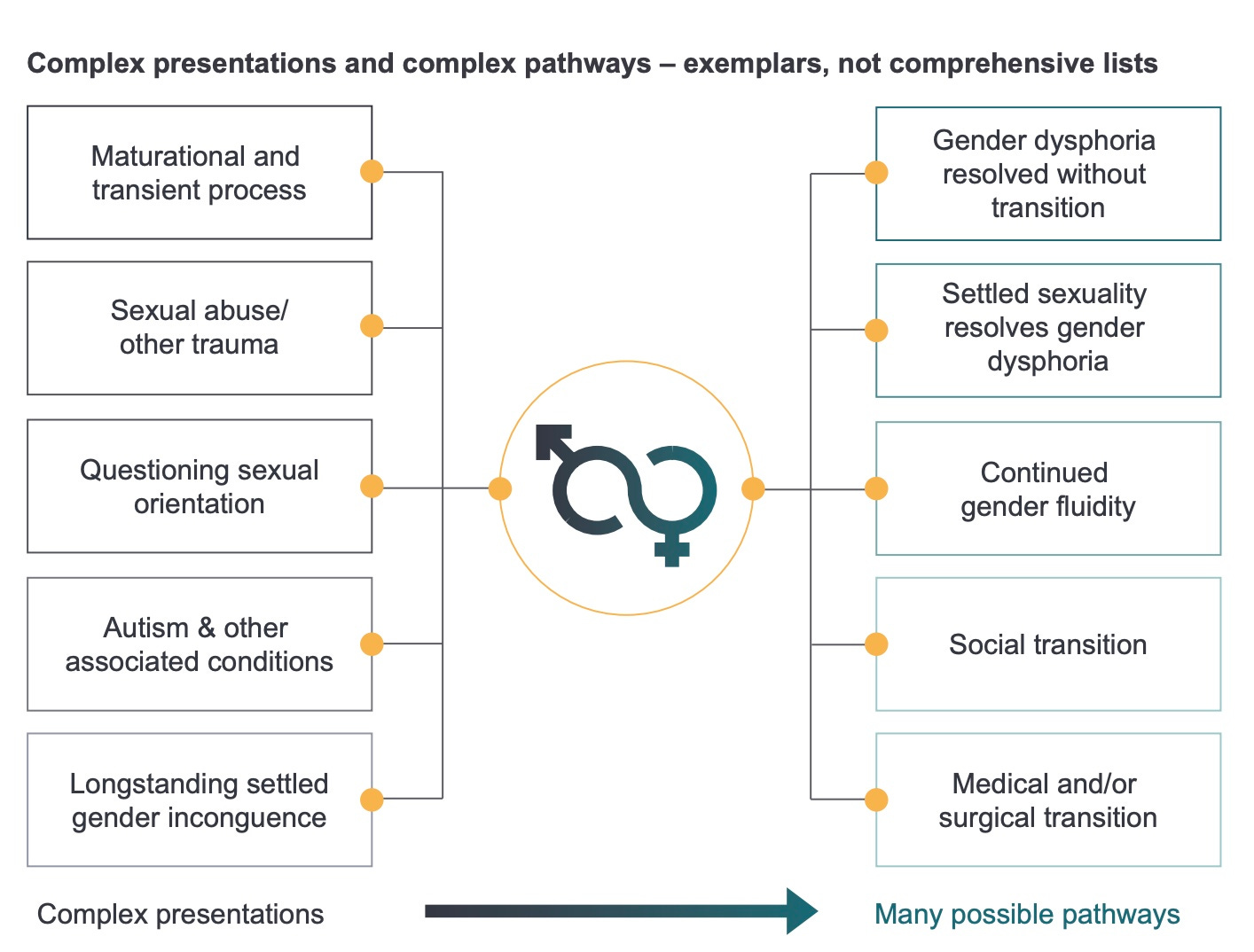

The context is rapid growth in atypical cases of gender dysphoria appearing chiefly among teenage females, as opposed to the classic presentation in minuscule numbers of mostly boys in early childhood.

Today’s gender clinic patients often come with pre-existing mental illness, autism, family dysfunction or awkwardness about same-sex attraction, raising questions about the true cause of distress and the right treatment.

A growing number of “detransitioners” who regret life-altering treatment are emerging internationally, and the affirmative medical model is under increasing challenge from health authorities, clinicians favouring an exploratory approach, parents’ groups and negligence lawyers in several countries.

The world’s largest affirmative gender clinic for minors, the London-based Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS), is to close, following an independent review led by paediatrician Dr Hilary Cass. The plan is to replace the stand-alone GIDS with a wholistic treatment approach in regional centres that are more safely anchored within mainstream mental health.

“From the point of entry to GIDS there appears to be predominantly an affirmative, non-exploratory approach, often driven by child and parent expectations and the extent of social transition that has developed due to the delay in service provision,” Dr Cass said in her interim report.

“There is limited evidence of mental health or neurodevelopmental assessments being routinely documented [at GIDS], or of a discipline of formal diagnostic or psychological formulation.”

Watch: Jennifer Lahl’s documentary Trans Mission

The detail

Affirm, affirm

On the APS website, the policy entry point is a webpage headed “Mental health practices that affirm transgender people’s experiences”. The first therapeutic response recommended by the APS is to “affirm a person’s gender”.

A link calls up a three-page position statement claiming that “a growing body of empirical research has demonstrated that affirming clinical responses can make a significant positive contribution to the mental health of transgender people”.

“As a professional organisation committed to evidence-based practice, the Australian Psychological Society therefore opposes any forms of mental health practice that are not affirming of transgender people,” the undated document says.

It endorses treatment and research into gender distress but prefers research within the “minority stress” model, where a bigoted society is supposedly to blame for poor mental health among trans people. The document restricts treatment to “affirming responses”.

It goes on to list affirmation of the client’s gender and referral for hormonal or surgical interventions as “evidence-based strategies” which are “equally applicable to children and adults”. The differences studied by developmental psychology are not mentioned.

“Psychologists working with both groups should always be guided by the client’s expressed needs,” the document says.

It implies that the only alternative to the affirmative model is a ‘“coercive” attempt to “direct” trans people to live in accordance with birth sex, and ignores the long tradition of neutral, exploratory psychotherapy.

The document cites the APS Code of Ethics and the 2014 Ethical Guidelines on Working with Sex and/or Gender Diverse Clients but neither of those documents mandates an “affirmation-only” approach to clients.

Gender explorers

Ideological capture of health professional societies has led clinicians and other interested people to establish their own groups, such as the Gender Exploratory Therapy Association (GETA), Thoughtful Therapists, the Clinical Advisory Network on Sex and Gender, Active Watchful Waiting Australasia, and the Gender Dysphoria Alliance.

GETA co-founder Stella O’Malley, an Irish psychotherapist, recently explained in Quillette magazine the difference between the affirmative and exploratory approaches.

“Gender-exploratory therapists do indeed ‘affirm’ the existence of individuals’ feelings and beliefs, as well as their wish to live as authentic beings. What we do not do is confirm these beliefs as based on fact, which is what the affirmation model effectively would require.

“Therapists hold a position of responsibility, and it is typically not a therapist’s role to confirm any beliefs or emotions pertaining to the client. A therapist who confirms a client’s belief risks exerting undue influence on the client at a time when he or she is in an emotionally vulnerable state.

“It usually makes more sense for the therapist to hold neutral therapeutic space, so that the client can more easily assess his or her beliefs independently.”

Last year, Australia’s trans health lobby AusPATH issued a public defence of the gender-affirming approach as “vital for maintaining good mental health”.

Methods matter

Australian psychologists told GCN that the gender-affirmative model did not fit easily within the profession’s empirical methods.

“The thing about affirmation is that an affirmation is an intervention in itself,” one clinical psychologist said.

“And so there's already been a decision made when someone presents about what the outcome will be.

“And that's highly problematic to psychologists, because it erases the need for assessment, and there's no need for case formulation because you already know what your intervention is going to be — it's going to be affirmation under all circumstances.”

Social transition before puberty, with adults affirming an opposite-sex identity, may prevent a child’s bodily distress from self-correcting, and may make medical intervention more likely, according to the literature on gender dysphoria.

Another clinician told GCN that the APS had not kept up with recent international evidence, including systematic reviews of the medical literature leading to Sweden’s decision to end paediatric transition as a routine treatment, and to the United Kingdom’s plan to close the Tavistock GIDS clinic.

The clinician said the APS affirmation policy was “giving very explicit directives about how psychologists should work, without having an evidence base that supports that level of confidence in their recommendations”.

And these directives were at odds with standard psychological practice in any area other than gender.

“It makes us look foolish, I think, in the eyes of our clients, who are probably ‘psychology savvy’ enough these days to know they should be getting an assessment, they should have a case formulation, they should have a treatment plan.”

In the affirmative worldview, the mental health symptoms of gender clinic patients are often said to reflect the transphobia of non-affirming families and society.

“[The APS affirmative policy] takes no account of conditions like autism, it takes no account of trauma and abuse histories, it takes no account of psychosis, it takes no account of really significant multi-layered issues that as psychologists we take into account whenever we're treating our clients.”

The clinician highlighted research linked to The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, which found that gender patients had high rates of anxiety, depression, suicidal ideas, behavioural disorders, autism and “adverse childhood experiences” such as family conflict, exposure to domestic violence, parents with mental illness, loss of important figures through separation, and bullying.

Despite this complexity, the Westmead study reported that gender clinicians were under increasing pressure to enable “conveyor belt” medicalisation of children amid expectations that this was the solution offered by the affirmative model.

“Families tended to medicalise the child’s distress, attributing it solely to gender dysphoria as an isolated phenomenon, with the consequence that the family identified the medical pathway as providing the only potential way forward,” the Westmead paper said.

But there was simply no good quality evidence to recommend medicalised gender change for today’s often very troubled teenage patients, a senior psychologist told GCN.

“We have evidence that it damages young people, makes them infertile. They become lifelong patients based on the increased risk of a whole lot of illnesses from cancer to thromboembolism.”

The psychologist said children could not give informed consent to hormonal treatments — hormone suppression drugs early in puberty blockers, followed by opposite-sex hormones — likely to leave them sterilised and unable to orgasm.

“To say that someone at age 12 accepts they may never have children, and they may never have sexual pleasure — it’s meaningless to a 12-year-old,” the psychologist said.

Diagnostic shadows

July’s news that the Tavistock GIDS clinic was to close brought a renewed focus to failings identified in Dr Cass’s interim report.

This month, 14 signatories — including clinical psychologists who had worked at GIDS and seen its shortcomings up close — wrote a letter to the British Psychological Society’s magazine The Psychologist.

They claimed the Society’s response to the Tavistock scandal had been “profoundly inadequate”, failing to acknowledge the severity of the problems at GIDS as a “psychology-led service”, or the harm done to some young people.

“[Dr Cass’s interim report] recommended a new service model which acknowledges multiple routes in and out of gender dysphoria. Elevated rates of same-sex attraction, autism spectrum disorders, mental health issues, and looked after children were noted amongst the — now majority female and hugely increased — GIDS cohort,” the letter said.

“Dr Cass reported that ‘diagnostic overshadowing’, using gender as the primary clinical lens, had led to such wider issues being relatively neglected. The new model intends to re-centre the young person’s needs, taking a holistic view of their difficulties.”

“This is a sobering moment for psychology. We need to take seriously that damaging practice was enabled for so long. Hundreds of psychologists worked at GIDS — highly trained scientist-practitioners skilled in reflective practice. Hundreds more have watched this unfold from the outside. Why did it take an external review to address the widely aired problems? Why was the service not able to reflect and change itself, instead vilifying critical voices?”

Policy at work

In a 2019 Tasmanian law reform inquiry, the Australian Psychological Society urged an affirmative stance on trans surgery, such as mastectomy, for children under 16 and discouraged “gatekeeping” by health professionals.

The Society argued against a proposed requirement that under-16 trans surgery not be allowed to go ahead without mandatory counselling and sign-off from two medical practitioners (including clinical psychologists).

The APS submission said optional mental health support should be available, as long as it was affirming. It claimed that requiring independent assessments from two medical practitioners “may unnecessarily restrict access to services”, citing a “bottleneck” in access to health services and a shortage of trained staff.

The Society also called for measures to allow minors to authorise their own trans surgery when parents do not support this medical intervention.

“Such mechanisms may include hospitals petitioning courts for approval for treatment, engaging in advocacy work to gain parental support for treatment, and the availability of legal services to minors to prove [their maturity under the legal test known as] ‘Gillick competence’ so that they may authorise their own treatment,” the submission said.

Maleficence

GCN understands that the APS leadership was alerted to the international debate about youth gender medicine after a surprising complaint of “transphobia” levelled by trans rights advocates against clinical psychologist Dr Sandra Pertot.

In an APS podcast interview, Dr Pertot had said she felt there was a lack of clarity about how to assess whether a client’s distress was gender dysphoria or something else. She suggested listening to detransitioners for clues about how to manage differential diagnosis and avoid treatment regret.

The APS leadership took the view that any treatment policy had to be open to criticism, yet the Society had recently adopted an affirmation-only approach.

That affirmative policy statement ends with a warning: “Psychologists are responsible for their professional decisions and may be liable to investigation for professional misconduct if a client makes a claim of maleficence [the doing of evil or harm]”.

The punitive tone of the policy document and its implication that any alternative to the affirmative approach is “conversion therapy” — outlawed in three Australian jurisdictions — would have the perverse effect of making clinicians avoid clients seeking help for gender distress, a senior psychologist told GCN.

Another clinician deplored the irresponsible use of dramatic but low-quality statistics on suicide risk.

“One of the most disturbing things about the current policy is the use of emotional manipulation on parents to say that if you don't go ahead with this [affirmative treatment], your child will suicide,” the clinician said.

In August 2019 in the APS magazine, InPsych, psychology academic Dr Damien Riggs declared that “clinicians and researchers who adopt less than affirming approaches to trans and non-binary people operate in something of a grey area.

“Parents may struggle to affirm a trans and non-binary child and may seek support from clinicians who are less than informed about best practice.”

He suggested that psychologists had a duty to alert child protection authorities to those failing to “affirm” a trans-identifying child who is seeking treatment such as puberty blockers.

“… it behoves all clinicians as mandated notifiers to consider when less than affirming approaches (either on the part of other clinicians or on the part of family members) may constitute forms of neglect, and to make reports as needed to the relevant bodies to ensure that young people receive the affirming clinical care that they need,” he said.

Hive mind

In his contribution to InPsych, Dr Riggs also rejected the hypothesis that social contagion online and via peer groups is a factor in the recent international surge in teenage females suddenly declaring a trans identity and wanting gender medicine.

American public health researcher Dr Lisa Littman used the term “Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria (ROGD)” to describe this theory.

In his article Dr Riggs, an APS fellow and a champion of the affirmative model, said ROGD was “a concept used largely by people who question rather than affirm young people’s gender”.

He said the Littman study suffered from a biased sample, offered an unrecognised “pseudo diagnosis” and had been “significantly revised due to community feedback”.

The Littman paper was open about the sample’s targeted nature, cautiously proposed ROGD as a hypothesis worth further research, and it was after pressure from trans rights activists that the journal contrived a post-publication “correction” leaving her findings essentially unaltered.

Dr Littman’s research on ROGD and detransitioners has been cited as plausible by prominent clinicians and reviews of gender dysphoria care internationally. Testimonials from detransitioners and parents of gender-questioning children are also consistent with ROGD as a new phenomenon.

In September 2019, the APS issued a media statement quoting Dr Riggs “refuting” the possibility of social contagion affecting gender identity claims.

It was not clear why gender alone would be immune to social contagion, which is a well-established concept in psychology and has been documented in teenage females with conditions such as anorexia and non-suicidal self-harm.

Pediatric pushback

In the United States, the American Academy of Pediatrics has been forced to defend its 2018 affirmation-only policy as criticism that began three years ago in the scholarly domain spills over into mainstream media and AAP membership forums.

Last week in The Wall Street Journal, the AAP president Dr Moira Szilagyi said that to “affirm” a child of teen affirmative care “means destigmatizing gender variance and promoting a child’s self-worth … It doesn’t push medical treatments or surgery; for the vast majority of children, it recommends the opposite”.

However, the AAP has refused to entertain requests for the 2018 policy to be put to the test of a systematic review of the evidence on youth gender dysphoria. And the AAP has yet to respond to the 2019 peer-reviewed “fact-checking” critique by clinical psychologist and researcher Dr James M. Cantor.

In his paper, Dr Cantor said his curiosity was piqued by the AAP deciding to adopt an affirmative-only position rather than the more cautious “watchful waiting” approach alert to the lesson of the literature that most dysphoric children would outgrow their distress.

“As I read the works on which they based their policy, however, I was pretty surprised — rather alarmed, actually: These documents simply did not say what AAP claimed they did. In fact, the references that AAP cited as the basis of their policy instead outright contradicted that policy, repeatedly endorsing watchful waiting,” Dr Cantor said.

“In its policy statement, AAP told neither the truth nor the whole truth, committing sins both of commission and of omission, asserting claims easily falsified by anyone caring to do any fact-checking at all.”

Note: GCN sought comment from the APS, the AAP, Dr Riggs and a prominent clinical psychologist who uses the affirmative treatment approach.

Brilliant analysis as always Bernard. Thanks for sticking up for Australian kids, despite the cost.

‘Until recently, the APS leadership had not realised the extent or gravity of the international debate about youth gender medicine, GCN understands.’

One wonders how and why they are not part of international conversations.