Mother's milk

Grief at the loss of breastfeeding shouldn't be a taboo subject

It is unethical for surgeons to perform a transgender mastectomy without warning patients they may never be able to give children the health benefits and close bonds that come with breastfeeding.

This is the argument of a new journal article reporting what is believed to be the first detailed account of a woman who identified as a trans male and had her breasts removed, only to “detransition”, achieve pregnancy and suffer “intense grief” at not being able to breastfeed her child.

“Elizabeth”, who was 20 at the time of the mastectomy, recalls no discussion with her surgeon about the likely loss of breastfeeding, while trans treatment guidelines and “chest masculinisation” research fail to consider the effect of surgery on breastfeeding, according to the article.

“It is surely unethical — and arguably negligent — for surgeons to remove an organ without explaining the functional effect to patients,” the article says.

“Proper discussion is required for the patient to choose and consent.

“It has been falsely claimed it is not possible to predict breastfeeding outcomes after chest masculinisation surgery based on surgical technique.”

The article discusses various techniques and complications, and concludes that “many, if not most, individuals who have undergone chest masculinisation mastectomy, are unlikely to retain ability to both produce and extract milk.”

The article appears in the journal Frontiers in Global Women’s Health and its authors are researchers Dr Karleen D. Gribble, affiliated with Western Sydney University (WSU); Emeritus Professor Susan Bewley of King’s College London; and Professor Hannah Dahlen of WSU.

There is an unprecedented international surge in chiefly female teenagers identifying as trans or non-binary, and seeking hormonal and surgical interventions which they believe will ease the “gender dysphoria” they feel in their bodies.

Girls as young as age 13 have had mastectomies — known on social media as “top surgery” — on the grounds that their breasts trigger dysphoria and contradict their inner “gender identity” as non-females.

In Elizabeth’s case, she developed breasts at age 10, was teased by other children and sexually harassed by adult males, leading her to hate her breasts. At age 15 she heard about the idea of gender identity, and attributed her bodily discomfort to being trans.

But there are increasing reports of young women like Elizabeth who came to decide that medicalised gender change was a “terrible mistake”.

The 2019-21 legal case of British detransitioner Keira Bell, who launched a judicial review action against the world’s largest youth gender clinic, the London-based Tavistock centre, has raised awareness about trans treatment regret.

“The consequences of what happened to me have been profound: possible infertility, loss of my breasts and inability to breastfeed, atrophied genitals, a permanently changed voice, facial hair,” Bell wrote in 2021.

Although the risk of sterilisation reportedly does not deter many trans-identifying minors seeking hormonal treatment, surveys suggest that adult trans people often do wish to have their own children.

Video: Californian detransitioner Chloe Cole talks about her experience

More regret ahead

The new journal article by Gribble and her colleagues suggests that regret after trans mastectomy is likely to become more common, given the rapid increase in teenage females at gender clinics.

There are reports of this surgery on minors in many countries, including 13-year-olds at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, whose gender clinic director Dr Johanna Olson-Kennedy once said that if adolescents “want breasts at a later point [they] can go and get them.”

The Gribble article points out that the average time for trans treatment regret to manifest itself in one large study was 10 years, and short follow-up time is one of several limitations in research invoked to downplay the scale of the detransition trend.

“Given that many women have their first baby in their 30s, there may be a decade or two between surgery and pregnancy during which regret may surface,” the article says. “In the future, there may be many mothers without breasts, needing support around inability to breastfeed.”

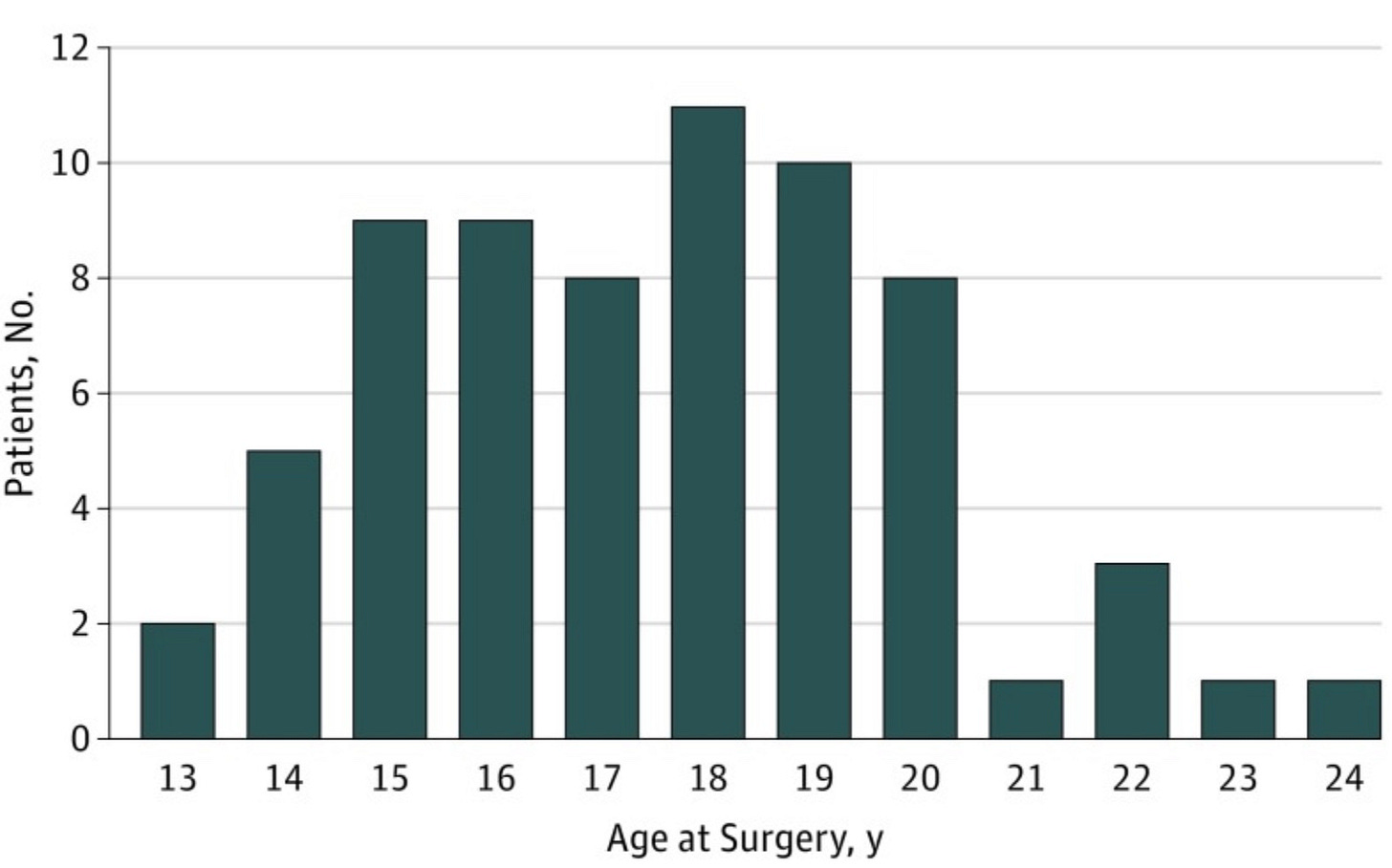

Chart: Age of patients given “chest reconstruction” surgery in a study at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles

Post-op problems

In recent surveys of female detransitioners, more than a third had undergone “chest masculinising mastectomy.”

Elizabeth’s detransition story had much to do with the disappointing outcome of her surgery, including one nipple graft leaking watery fluid, a build-up of smelly paste in the other, scarring and nerve pain.

Trans friends urged her not to tell others about this because “you’re making trans surgery look bad,” the Gribble article says.

“The failure of the surgery to fulfil its promise, concurrent with rejection by transgender friends and testosterone-induced vaginal atrophy, resulted in a psychological crisis.”

Elizabeth admitted that at the time, she would not have been open to a warning about the surgical risk to breastfeeding and would have protested any such talk “was triggering my gender dysphoria.

“That wouldn't really have been true,” she told Dr Gribble. “It would have been because … maybe I did want children … but it’s like this trump card, gender dysphoria, meaning you can't have any conversation [to explore difficult issues] … gender dysphoria is something that can conceal more than it reveals”.

When Elizabeth’s new-born son was placed skin-to-skin on her chest, he instinctively hunted for her breast — “it was really hard knowing that he wanted to breastfeed, and I couldn't give him that … he spent so much time in his early life trying to find my breasts.”

Elizabeth is in her 30s, her son would be primary school-age, and she is still worried about the health risks of the synthetic testosterone she took as a trans man— “I'll never be able to forgive myself for whatever potential effects of testosterone that I took might have had on my eggs and affected my son including, epigenetic changes [involving interaction between genes, behaviour and environment] … who knows what that [testosterone] did?

“I'm really sad that there's going to be so many women, many of whom are children today, who are not going to be able to have children of their own because they're being sterilised.

“And I'm very frustrated that it's taboo to talk about that … I am speaking because I want to spare future mothers and babies what we went through, if I can.”

Guidelines without guidance

The Gribble article says the 2022 Standards of Care from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) fail to recommend pre-surgery counselling on breastfeeding, and nor do guidelines from the Australian and New Zealand bodies affiliated with WPATH.

The 2020 Australian Standards of Care and Treatment Guidelines for gender dysphoria care issued by the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne (RCH), home to the country’s biggest and most influential gender clinic, say that trans mastectomy “may be appropriate” for adolescents but make no mention of the breastfeeding issue.

The document says that “chest reconstructive surgery is regularly performed across the world in countries where the age of majority for medical procedures is 16 years.”

In 2019 a royal commission into mental health was told that “many” of the RCH gender clinic’s recent intake of “post-pubertal trans males” [biological females] wanted this surgery, which was “an integral part of the [gender] transition”. (The clinic takes patients up to age 17.)

The Gribble article notes a 2022 editorial in the highly ranked journal JAMA Pediatrics bearing the title, “Top surgery in adolescents and young adult — effective and medically necessary.”

The editorial ran in tandem with a Chicago study of the psychological outcome of trans mastectomy on a group of 14-24 year olds — with a 14 per cent drop-out rate and only a three-month follow-up.

“[The researchers] argued that there is no evidence to support delaying chest masculinisation mastectomy based on age and claimed that their findings would, ‘help dispel misconceptions that gender-affirming treatment is experimental’,” the Gribble article says.

It says the claims made by the Chicago study and JAMA Pediatrics editorial “cannot be substantiated and call into question whether there has been a failure of peer review and the editorial process.

“Children and young adults with gender dysphoria deserve a good research basis for their treatment and a critical consideration of the risks and benefits of procedures like chest masculinisation mastectomy.”

Video: A regulatory body, the British Columbia College of Nurses and Midwives, brought charges against nurse and mother Amy Hamm for speaking out in favour of women’s rights based on biological sex

‘Chestfeeding’

While trans surgery endangers breastfeeding, some health agencies encourage biological males who identify as women to somehow mimic this maternal role, with unknown effects on children.

The website of the breastfeeding organisation La Leche League International says: “Trans men, trans women [biological males], and non-binary individuals [of either sex] may choose to breastfeed or chestfeed their babies.

“You do not need to have given birth to breastfeed or chestfeed, as we can also see in the experiences of those nursing adopted babies.”

A 2020 study in the International Breastfeeding Journal surveyed 82 gender clinicians at the 2018 WPATH symposium in Buenos Aires, and reported that 34 per cent had met trans women interested in inducing lactation with medicines or other means.

“Respondents reported two specific protocols [for chemically inducing lactation in trans women], however there is no data to demonstrate efficacy or safety of either protocol,” the study says.

A 2021 LGBTQIA+ guide from the Australian Breastfeeding Association and a group called Rainbow Families says: “Lactation is very flexible and can work in many different situations … A person may make milk and feed a baby after surgery or hormone replacement therapy. How you feed your baby is your decision.”

The guide uses “inclusive” terms such as “birthing parent”, “chestfeeding” and “human milk feeding”.

It poses a question — “Do I need to stop taking hormones?” — for mothers who identify as male and who take synthetic testosterone to masculinise their bodies.

The guide’s answer: “This is a new area of study and so caution is advised. There could be unknown risks involved with lactating during or after taking hormones … Decisions concerning hormones and feeding a baby need to be considered carefully, with the support of a medical professional.”

A document from the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne touching on fertility preservation for trans-identifying adolescents says it is “currently unknown” the degree to which fertility is “permanently impacted” by the opposite-sex hormones testosterone and oestrogen.

It says most females will resume menstruation 3-6 months after testosterone drugs are stopped, and “natural pregnancies have been seen while still on testosterone.”

The document offers a warning: “Testosterone is teratogenic [causing birth defects], and [trans] men [who are biologically female] should be advised to use contraception if they have a male partner.”

The LGBTQIA+ Rainbow Families guide equivocates on whether or not the risk to breastfeeding from mastectomy is foreseeable, saying: “Any surgery on the chest, milk-making tissue, nipple, and/or areola could affect lactation. Because surgery techniques vary widely, even within the same procedure, it is hard to predict how your individual surgery will affect your chances of making milk.”

Some trans men (biological females) may decide to take medicine to suppress lactation, according to the guide, which says, “If this is advised, talk over the pros and cons of using them with your doctor, as there are some risks to their use.

“When some people think of feeding from the body [breastfeeding] and parenting, they think of femaleness, a womanly figure, and strong mothering identity. This is often not the case for transgender and gender diverse people.”

The guide suggests that while breastfeeding may cause some mothers dysphoria, others may discover its pleasures.

“Making milk for a child is a life transition and brings changes to hormone levels that can affect mood and bonding. Your feelings around feeding may change in ways that surprise you.”

So disappointing to note that zero midwifery or breastfeeding organisations in Australia spoke up for vulnerable young women like Elizabeth when demands for gender affirmation without question were made.

quackery