Gender movement

Change of leadership at Australia's largest youth gender clinic

Australia’s high-profile advocate for the “gender-affirming” treatment approach, the paediatrician Dr Michelle Telfer, has reportedly stepped down as director of the country’s largest and most influential gender clinic until mid-2023.

Colleagues have been told that she is to serve for six months as acting chief medical officer — a senior management position — at the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) Melbourne.

Her last day as director of the RCH gender clinic — and of the adolescent medicine department at the hospital — was December 16, but she will keep seeing patients at her outpatient clinic, GCN understands.

Psychiatrist Dr Tram Nguyen and paediatrician Dr Cate Rayner are reportedly to run the clinic until Dr Telfer’s expected return as director in the middle of next year.

[Update, April 2023: In belated changes to its website RCH has confirmed Dr Telfer’s December 2022 appointment as chief of medicine. Dr Rayner has been listed as acting director of the gender clinic, while Dr Nguyen remains part of the team.]

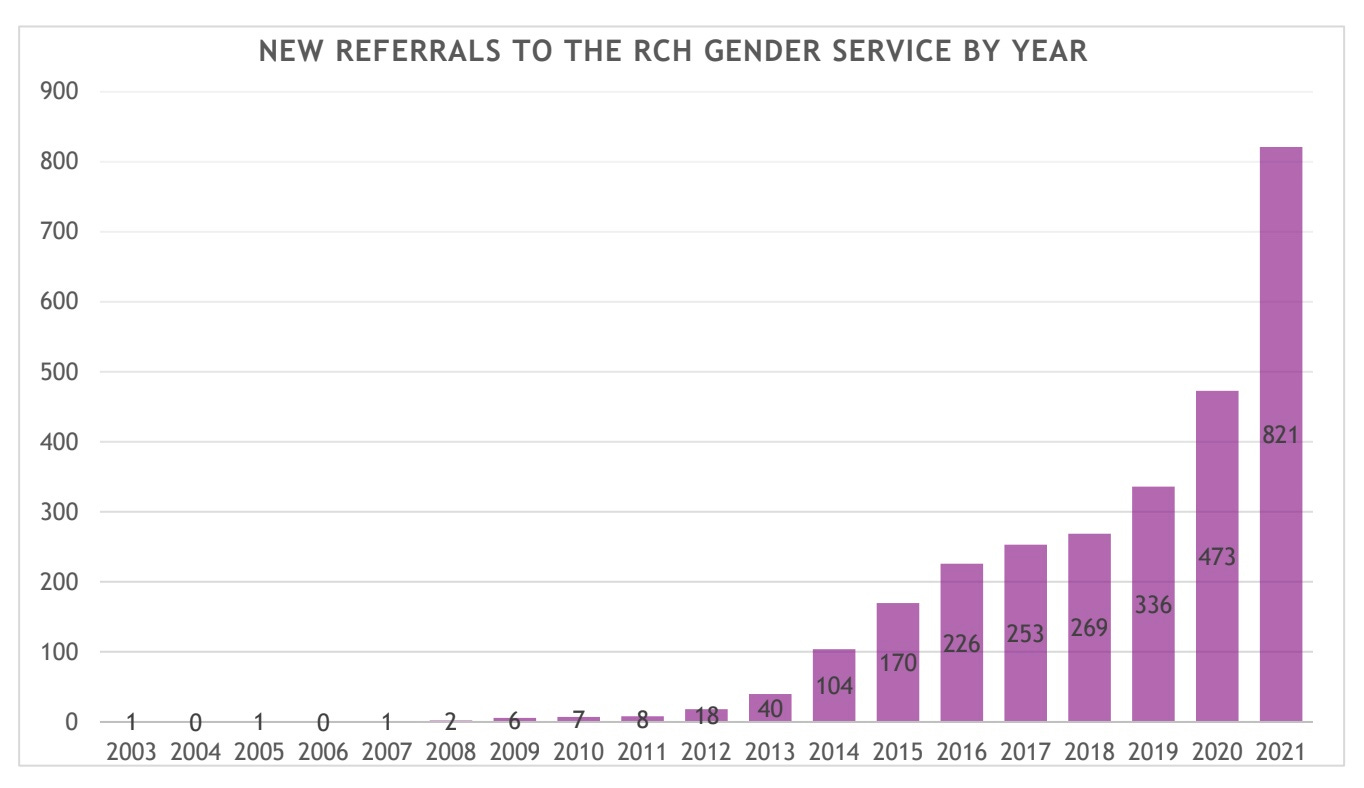

In 2012, when Dr Telfer was appointed director, the gender clinic had 18 new referrals; last year there were 821.

Dr Telfer has been the public face of the RCH gender clinic, which is one of three large gender services in the country’s public children’s hospitals. She has also been the Australian figurehead for the increasingly contested “gender-affirming” treatment approach to youth gender dysphoria, a distressing sense of conflict between a felt “gender identity” and the body.

It’s not clear if the change in roles for Dr Telfer will affect the planned revision of the 2018 RCH treatment guidelines, which are badged as “Australian Standards of Care”. In May, she announced she would lead this first major revision.

Dr Telfer is also involved as a principal investigator in the gender clinic’s Trans20 longitudinal study of 618 minors, aged between 3 and 17 years old, first seen at the RCH clinic between 2017 and 2020, and having received gender-affirming interventions. The study lacks a comparison group of participants given alternative treatment such as the “watchful waiting” approach.

A 2019 protocol for the study said there was “limited empirical data” on the rapidly growing number of teenage gender patients and “an urgent need for more evidence to ensure optimal medical and psychosocial interventions.”

Initial Trans20 data published that year showed a disproportionate number of biological females (275, with a mean age of 13.6 years, of a total 383 participants), high rates of mental health problems, a history of bullying and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Mild to severe autism features — not necessarily leading to a formal diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder — were reported in 45 per cent of participants.

Full results of the Trans20 research project are yet to be published.

Affirmative campaign

The 2017 Family Court ruling in the gender medicine test case known as Re Kelvin and the associated development of the RCH treatment guideline represented a high-water mark in the Australian campaign to promote the hormonal interventions of the gender-affirming model and to wind back judicial oversight of a child’s capacity to give informed consent to these life-altering treatments.

In 2018, The Lancet ran an unsigned editorial endorsing the RCH guideline — with the heading “Gender-affirming care needed for transgender children” — and noted RCH advice that social transition — stepping into an opposite-sex role — should be child-led. (Sceptics say early social transition risks locking in the distress of gender dysphoria.)

At a 2019 royal commission into mental health in the state of Victoria, Dr Telfer lobbied for secure, long-term funding so that her children’s hospital could begin to offer “chest reconstruction surgery” — double mastectomy — which she said was “an integral part of the transition process” for biological females who identify as trans males.

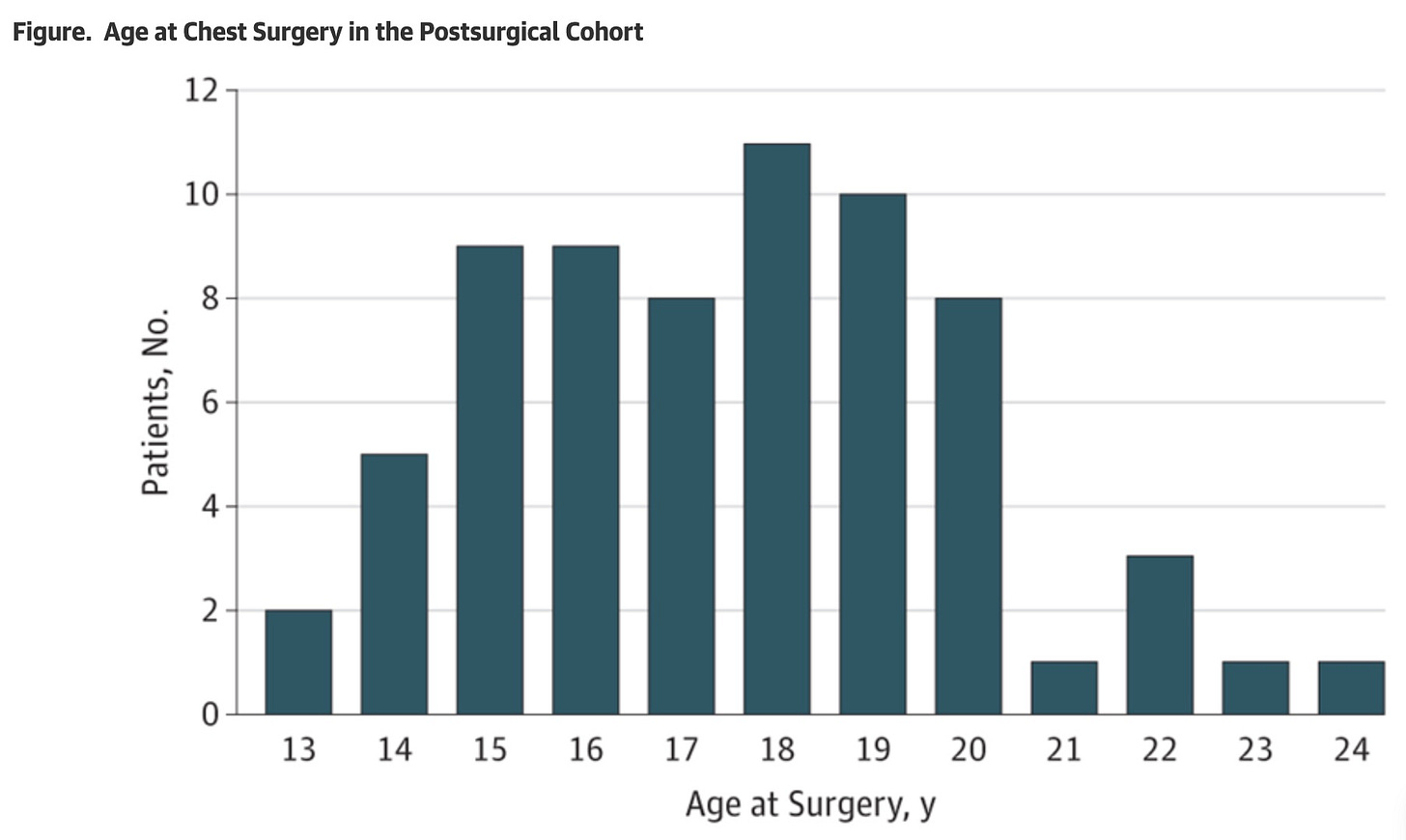

She told the commissioners that this surgery would “improve mental health outcomes”, and cited a 2018 American study in JAMA Pediatrics which reported a decline in “chest dysphoria” after trans mastectomy undergone by 68 biological females aged between 13 and 24 years of age; 16 of these patients were under the age of 16.

Australia’s Family Court has authorised mastectomies for minors as young as 15 years of age. The number of trans surgical interventions with patients under age 18 is thought to be small but there is no good data.

In response to media questions, RCH management said in May 2021 that there were “no plans” to use a fresh injection of public funds to begin trans mastectomy at the hospital.

In November last year, the hospital said it was “not aware” of the gender clinic referring any patients to private surgeons for this procedure. The clinic takes patients up to the age of 17.

The RCH clinic, its director, campaigns and medical interventions have been promoted by progressive media with little or no reference to the international debate about youth gender medicine.

Australia’s public broadcaster, the ABC, has for several years presided over news and current affairs programs showcasing gender-affirming treatment without any detailed scrutiny of the evidence base.

Turning of the tide?

Since 2019, there has been a marked increase in international media scrutiny of gender clinics and intensifying expert debate over the evidence base and safety of puberty blockers, opposite-sex hormones and trans surgery for minors with immature brains. (Puberty blocker drugs interrupt natural but “unwanted” puberty, while synthetic hormones masculinise or feminise the body.)

The Family Court’s one-sided reliance on expert witnesses advocating for the gender-affirmative treatment approach has come under challenge, and gender medicine is expected to face more litigation internationally as regretful “detransitioners” multiply.

In 2020, after a systematic review of the medical literature, Finland concluded that the evidence declared the evidence base was so poor that medicalised gender change for minors was “an experimental practice”, and health authorities there made psychosocial interventions the first-line treatment for youth gender dysphoria.

New treatment guidelines in Sweden, published earlier this month, confirm that country’s February 2022 shift to caution, with puberty blockers and opposite-sex hormones for minors confined to research settings.

Puberty blockers — still given as routine treatment in Australia — would also be restricted to formal research in England under draft treatment plans for youth gender dysphoria care following the closure of the London-based Tavistock gender clinic, which was the world’s largest such service.

Systematic reviews in Finland, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the American state of Florida have all concluded that the evidence base for the medical transition of minors is weak and uncertain.

Note: GCN has sought comment from RCH and Dr Telfer. In 2019, the hospital said its gender clinic treatment was based on the “best available medical evidence”, in line with “international best practice”, and followed “strict clinical governance standards”. GCN does not dispute that gender-affirming clinicians believe their interventions are of benefit to vulnerable patients in distress.

‘Flimsy’ evidence

A new report from the British organisation Sex Matters concludes that the evidence for gender-affirming interventions is “lacking.”

“Perhaps the most critical issue with the evidence base is that findings are often reported in the academic literature as fact, when going back to the original research shows them to be as flimsy as a house of cards,” says the author Matilda Gosling, an independent social research consultant.

“These ‘facts’ are then cited by another study on the basis of how they were reported, not on what the research actually shows. One group of scholars describes this as a game of Telephone ‘in which a message is whispered from person to person distorting the original meaning of the message. However, this is not a game, and these types of errors can cause harm.’

“Teenagers on puberty blockers are shorter than their peers, on average, and they have both less muscle and more body fat. They tend to have lower bone density than other teenagers, an effect that remains even once they no longer take puberty blockers. Although bone density may increase during hormone treatment, young people who have been on a combination of puberty blockers and hormones have lower bone density than they would have done without treatment. Adolescence is a key period for the development of bone mineral, meaning these teenagers may be at higher risk of developing osteoporosis when they are older.

“The effects of puberty blockers on brain development are not yet known, but they may be negative. One large-scale study of British teenagers finds that those who go through a late puberty have lower cognitive skills and worse educational attainment than their peers; while this shows correlation, not causation, it is worth noting in the absence of studies specific to the long-term effects of puberty blockers.

“According to scholars who reviewed existing research in this area, ‘The combination of animal neurobehavioral research and human behavior studies supports the notion that puberty may be a sensitive period for brain organization: that is, a limited phase when developing neural connections are uniquely shaped by hormonal and experiential factors, with potentially life-long consequences for cognitive and emotional health.’

“While loss of fertility is not an impact of puberty blockers if children resume normal puberty after taking them, there is no way for them to become fertile as adults if they have never been through the puberty that relates to their sex.

“This is because the cells that go on to form ovaries and sperm will not have been able to mature. And as almost all children who take puberty blockers go on to take hormone treatment, later infertility, which is a key impact of hormone treatment, is almost inevitable.

“Taking oestrogen affects the healthy future development of sperm in those with a male reproductive system, and testosterone stops egg-bearing follicles developing in those with a female one.”