Explorers wanted

The post-Tavistock gender services will go deeper than mere affirmation of what a child tells them

Analysis

Gender affirmation 1; exploration 10

The “gender-affirming” ethos makes just one appearance in new plans for gender services to take over after the Tavistock clinic.

But exploration of a young patient’s various problems — not just gender issues but mental health disorders or autism, whatever troubles them — is repeatedly stressed in the draft “service specification” issued on October 20.

Activists have suggested that the key failing of the Tavistock was its long waiting list, that its closure is not bad news for other gender-affirming clinics around the world.

They point out that the stand-alone Tavistock is to be replaced with two clinics, and celebrate this as an expansion of the gender-affirming approach.

Well, now we have draft plans from the National Health Service for those new gender services based in London and in England’s north.

In this 26-page document, affirmation gets one reference — and it’s a discouraging one for clinicians and activists who put so much faith in the self-declared gender identity of children.

Socially trans

In the gender-affirming worldview, it’s a no-regrets, low-risk option to affirm a social transition, whereby the child or teenager takes on a new name and begins to live out an opposite sex identity.

The NHS disagrees, and insists that enabling social transition should not be seen “as a neutral act” but as an intervention in its own right with potential significance for a young person’s psychological functioning.

“In cases where a pre-pubertal child has effected, or is effecting, a social transition (or expresses a wish to effect a social transition) the clinical approach has to be mindful of the risks of an inappropriate gender transition and the difficulties that the child may experience in returning to the original gender role upon entering puberty if the gender incongruence does not persist into adolescence,” the NHS says. (Emphasis added.)

Risks include the possibility that social transition makes it less likely that children will outgrow distress (gender dysphoria) in the only body they have. The result can be lifelong medicalisation.

As for teenagers, the NHS also adopts a cautious approach to social transition. Before it can be considered, three conditions must be met — including a diagnosis of “consistent and persistent” gender dysphoria and the adolescent showing full comprehension of the implications of this step.

Video: Oxford sociologist Dr Michael Biggs and psychiatrist Dr Az Hakeem discuss youth gender dysphoria and puberty blockers

Known unknowns

The NHS is conscious of what cannot be predicted: which children will persist in dysphoria over the years, and which will desist and re-embrace their birth sex.

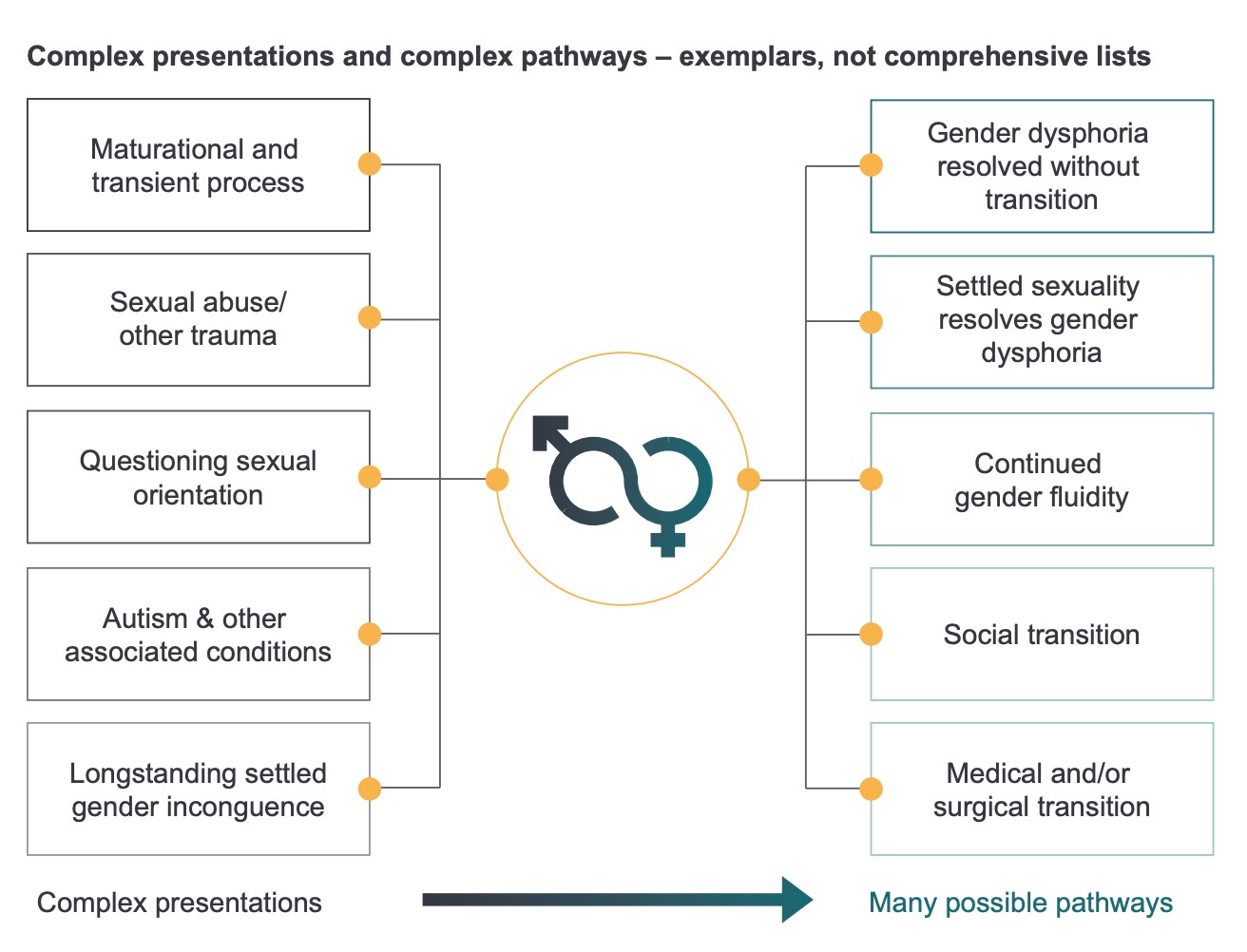

“The clinical management approach should be open to exploring all developmentally appropriate options for children and young people who are experiencing gender incongruence [between the body and a sense of ‘gender identity’], being mindful that this may be a transient phase, particularly for prepubertal children, and that there will be a range of pathways to support these children and young people and a range of outcomes,” the NHS says. (My emphasis.)

“The clinical approach in regard to pre-pubertal children will reflect evidence that suggests that, while young people who are gender querying or who express gender incongruence may have started their journey as younger children, in most prepubertal children, gender incongruence does not persist into adolescence.”

In sharp contrast, gender affirming clinicians claim that very young children can discern their transgender identity; mistakes and regret are played down.

One American psychologist — associated with Harvard University and the gender clinic at Boston Children’s Hospital — has even proclaimed that “a good portion of children do know [their gender identity] as early as — seemingly — from the womb”.

More than 200 children referred to the Tavistock clinic last financial year were aged under 10. Total referrals rose 133 per cent to 5,234.

Progressive medicine

To appreciate the NHS shift to caution, consider by way of contrast the gender-affirming treatment guidelines said to be the first such document specifically for the care of children and adolescents.

This guideline from the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) in Melbourne was praised by The Lancet in an unsigned editorial in June 2018, beneath the headline “Gender-affirming care needed for transgender children.”

That buzzword “affirming” gets 49 mentions in the hospital’s treatment guideline.

On social transition, RCH says it “should be led by the child”. This passage has nothing to say about any risks in such a re-engineering of social reality. It simply remarks: “The number of children in Australia who later socially transition back to their gender assigned at birth is not known, but anecdotally appears to be low and no current evidence of harm in doing so exists.”

Evidence is a sore point for the gender affirmers.

The version of the RCH guideline published as a 2018 paper by the Medical Journal of Australia says: “The scarcity of high-quality published evidence on the topic [of youth gender dysphoria care] prohibited the assessment of level (and quality) of evidence for these recommendations.”

Recent systematic reviews of the medical literature — the same hormonal and surgical treatments are used internationally with minors —have confirmed that gender-affirming interventions rest on a weak evidence base.

On blockers

The NHS also departs from the gender-affirming way with puberty blockers. These drugs, which interrupt normal development, will only be available “in the context of a formal research proposal”. In short, they are experimental.

Dr Hilary Cass, the senior paediatrician leading an independent review of youth dysphoria care for the NHS, has been especially worried about the risks and uncertainties of blockers.

Do they put patients — as young as 9-13 years old — on a one-way path of medicalisation? What is their effect on the still-maturing adolescent brain? Are nature’s sex hormones — suppressed in the name of trans identity — necessary for time-sensitive cognitive changes?

The NHS argues that taking blockers out of a clinical setting and supplying them in the course of research “will ensure that there is greater transparency for children and their parents/carers around the uncertain clinical benefits and longer-term health impacts surrounding their use.

“[And the research setting] will further strengthen the consent and information-sharing process to support informed decision-making by young people.”

Which raises the question: is it possible for 9-13 year-olds to give informed consent in today’s gender-affirming clinics where blockers are offered as routine treatment?

Fertility for kids

The treatment guideline from RCH Melbourne says these children should be offered information and advice about “fertility preservation” before hormone suppression, because sterilisation is the expected outcome of early puberty blockade followed by opposite-sex hormone drugs.

“This [advice and information] will need to be tailored to the developmental stage of the adolescent, especially for those who are in the early stages of puberty who have limited understanding of reproductive biology,” the RCH document says.

It also notes that early puberty suppression for boys who identify as girls brings “a surgical disadvantage that arises from the reduced availability of penile and scrotal skin for creation of a neo-vagina”.

To this must be added the prospect of sexual dysfunction as adults. The U.S. gender surgeon Dr Marci Bowers has reported that boys who underwent hormone suppression early in puberty have proven incapable of orgasm.

Can all this be comprehended and weighed in the balance by a child of 9 or 10 years of age?

Earlier this year RCH’s newsletter to patients and parents announced its own research into hormone suppression and the brain, saying “we do not know whether using puberty blockers affects development of the brain”.

Even so, the hospital’s treatment guideline still maintains that puberty blockade is “reversible in its effects.

“Other physical changes such as linear growth and weight gain continue to occur whilst on these medications and the adolescent is given time to develop emotionally and cognitively prior to making decisions on gender-affirming hormone use which have some irreversible effects,” the document says.

The NHS abandoned that kind of confidence in June 2020, when it quietly changed its webpage advice on puberty blockers.

Gone was the claim that blockers are “fully reversible” — a reassuring guarantee still common outside the United Kingdom.

New material on the NHS webpage accentuates the unknown: “Little is known about the long-term side-effects of hormone [suppression] or puberty blockers in children with gender dysphoria.

“Although the [Tavistock clinic] advises this is a physically reversible treatment if stopped, it is not known what the psychological effects may be”.

No dogma

In keeping with this clinical humility, the NHS is seeking staff for its post-Tavistock gender services who have an “understanding of the contested debate” about how best to respond to youth gender issues, and an awareness of “the limited evidence base to inform clinical approaches and service delivery; and limited data on outcomes”.

At their most dogmatic, gender-affirming clinicians assert that any intervention other than the gender-affirming kind is unethical “conversion therapy” to be suppressed by criminal law.

Like Finland and Sweden, however, England is shifting to psychological interventions and social support as first-line remedies for young patients, with the aim to encourage an exploratory approach open to a range of options — not only gender transition.

The NHS says that work with pre-pubertal children “will focus on a careful observation of how gender dysphoria develops as puberty approaches and is reached.

“The therapeutic approach for younger and pre-pubertal children is not directed at gender dysphoria itself but instead focused on other clinical presentations and needs, or familial/social circumstances that may impact on the child’s psychological health and gender dysphoria.”

“Watchful waiting” — a time-honoured clinical approach of attentive patience, misrepresented by affirmative activists as “doing nothing” — is included by the NHS as an option.

Holistically speaking

Nobody disputes that youth gender clinics now see patients with a range of mental health disorders and other issues, but there is disagreement about how to interpret and respond to this complexity.

The gender-affirming model, unsurprisingly, holds out the promise that affirmation can help the trans patient prosper, notwithstanding a supposedly transphobic world.

“Increasing evidence demonstrates that with supportive, gender-affirming care during childhood and adolescence, harms can be ameliorated and mental health and wellbeing outcomes can be significantly improved,” the RCH guideline says.

And the hospital argues that poor mental health, even psychosis, “should not necessarily prevent medical transition in adolescents with gender dysphoria”.

This would surprise clinicians in Finland, a jurisdiction which was an early adopter of youth gender medicine yet moved to a more cautious policy in 2020, drawing on its own research and clinical experience.

“In adolescents, psychiatric disorders and developmental difficulties may predispose a young person to the onset of gender dysphoria,” the Finnish policy says.

“These young people should receive treatment for their mental and behavioural health issues, and their mental health must be stable prior to the determination of their gender identity.”

The Cass inquiry in the U.K. has drawn some of its lessons from Finland.

The NHS service specification says: “A significant proportion of children and young people who are concerned about or distressed by issues of gender incongruence, experience co-existing mental health, neurodevelopmental and/or family or social complexities in their lives.

“The relationship between these aspects and gender incongruence may not be readily apparent and will often require careful exploration.”

Affirmation, according to its critics, puts the spotlight on gender and overshadows other problems that need solutions.

Much of the detail in the post-Tavistock planning by the NHS has to do with a system of referral and collaboration between the new gender services and local health, with the aim that all the issues troubling these young people get attention.

“A care plan should be tailored to the specific needs of the individual following careful therapeutic exploration; this plan may require a focus on supporting other clinical needs [other than gender dysphoria] and risks with networked local services,” the NHS says.

Dr Cass made the case for “a fundamentally different service model”. That is what’s emerging, not more gender-affirming sameness.

The Royal Children’s Hospital Gender website, in the section titled ‘Puberty’ states:

Puberty blockers suppress the development of secondary sex characteristics and are used for adolescents in the early stages of pubertal development. As they are reversible in their effects, should an adolescent wish to stop taking them at any time, their biological puberty will resume.

Yet:

New material on the NHS webpage accentuates the unknown: “Little is known about the long-term side effects of hormone [suppression] or puberty blockers in children with gender dysphoria.

I have emailed the RCH on two occasions and advised that their statement on puberty blockers is misleading. I have received no response.